To make informed security decisions that move your company forward, you must first determine the current security settings.

Perhaps you’re new to IBM i security or security has been neglected for awhile and needs a reboot. In this article, I’ll explore the IBM i security features available to you and how I would use them to make decisions on how to proceed.

My business partner, John Vanderwall, and I have just started our own business again. To launch DXR Security, we needed to investigate the current business landscape and the tools available to determine how best to establish our new business (e.g., the current banking and accounting software, business partners with similar objectives, etc.). Basically, we had to do a reboot on the whole business startup process. Fortunately, we did this once before, when we started SkyView Partners, so we knew what to look for, but for entrepreneurs just starting out, the way would not be as obvious and much more research would be required.

What does this have to do with researching IBM i security settings? I believe some of you find yourself in a situation where you’re like entrepreneurs starting a business for the first time. You want to get started with IBM i security, but you don’t know what’s available to you in the operating system much less know where to start tightening down the settings. My intent with this article is to help accelerate your discovery process by describing the commands and tools IBM provides so you can easily gain an understanding of your current settings without having to do the research yourself. Then I’ll discuss the integrated utilities you can use to get started tightening your IBM i security configuration settings and generate reports to gain regular insight into these settings.

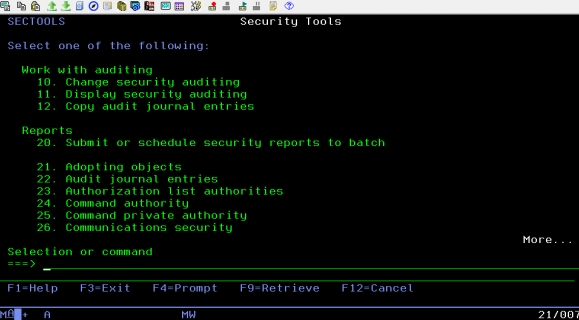

The best place to get a basic understanding of the security configuration are the commands, reports, and utilities provided on the Security Tools menu. The SECTOOLS menu lists numerous utilities and reports that will help you make an assessment of the system. Let’s take a look.

Figure 1: Type GO SECTOOLS to access this menu.

Option 1 is simply the Analyze Default Password (ANZDFTPWD) command, which produces a report listing any profile that has a password that is the same as the user profile name. Clearly, default passwords are something to avoid, so you’ll want to run this option to determine if this is a problem. I’m going to skip the rest of the menu options on this page for the moment and scroll down to the second page of the menu.

Figure 2: Page Down to get to this set of menu options.

I use menu option 11, Display security auditing, to determine what action auditing (if any) has been configured. I also use it to find the naming convention of the audit journal receivers. I can then run the Work with Journal Receivers (WRKJRNRCV) command to find out how many days’ worth of audit journal receivers are on the system—in other words, how many days of audit information are available without having to restore journal receivers from a backup. If you find that auditing has not yet been configured on the system, use menu option 10, Change security auditing, to do the initial setup. This will create the audit journal as well as create and attach the journal receiver and change the auditing system values for you.

Menu option 21 starts the Reports section. These options run commands that generate a variety of reports containing security-relevant information, including adopted authority (option 21), job and output queues (option 44), and trigger programs (option 47) to name a few. Menu option 46, System security attributes, provides a report of the current and recommended settings for the security-relevant system values and network attributes. I recommend that you run this report to get a quick view of these important settings. It also provides the recommended setting for each value. I personally don’t agree with all of the recommendations, specifically for the password and SSL/TLS-related system values. In addition, prior to changing any system value. I highly recommend that you investigate the implications of that change. You can read IBM’s discussion regarding changing system values in the Security Reference manual chapters 2 and 3. If you want my viewpoint, check out my most recent book, IBM i Security Administration and Compliance, Third Edition.

Other menu options run either the Print Public Authority (PRTPUBAUT) or Print Private Authority (PRTPVTAUT) command with a specific object type already defaulted. For example, if you want to know what the *PUBLIC authority setting is for each library on the system, you can simply run option 36, Library authority. Or, for both the *PUBLIC and private authorities to directories, you could run option 28, Directory private authority. All authorization lists can be reviewed by taking menu option 23 or by running PRTPVAUT OBJTYPE(*AUTL). When you’re trying to get a big picture of the system, using these commands directly or running specific menu options is far easier than running the Display Object Authority (DSPOBJAUT) or Display Authority (DSPAUT) command for multiple objects.

The last menu option I’ll point out is 49, User profile information, which runs the Print User Profile (PRTUSRPRF) command. Taking the defaults for this report will generate four reports in one. The first section lists authority information (profiles, their groups, special authorities, limited capabilities, etc.). The second report includes users’ initial program, initial menu, job description, etc. The third report includes password information such as the profile status, number of invalid sign-on attempts, whether profile has a password, password expiration interval, password last change date, and more. The fourth and final section can be ignored unless you’re down-leveling the system’s password level (which, hopefully, rarely happens).

The whole report can be a bit overwhelming, so let’s look at some of the areas I focus on. I typically focus on the first report, where I can easily tell if special authorities are out of control—that is, many users have been granted each of the special authorities. While it’s way too difficult with a printed report like this to physically count the number of profiles with the special authorities, I can easily scroll through the report and visually see the X’s in each column indicating the profile has been granted that special authority. I can also use this first report to see which group or groups the profiles are a member of as well as profiles’ limited capability setting. All of these are indicators of the overall configuration of user profiles. The next report I find helpful for this type of analysis is the third report. Specifically, I look at the profiles’ password expiration interval, looking for profiles with a non-expiring password as well as the indication of when the password has been set to *NONE. Group profiles and service accounts that are used only to run batch jobs or profiles created to own objects shouldn’t have a password; in other words, the password should be *NONE. This information, together with the information from the first report, allows me to quickly determine the overall condition of the user profiles on the system.

Now that you have a basic overview of your security configuration, let’s take a look at a couple of the utilities available on the SECTOOLS menu. Back on the first page of this menu, options 2–4 provide a utility that will disable profiles after xx days of inactivity, where xx is the number of days you specify when taking menu option 4. You can also eliminate profiles from ever being disabled by specifying them via menu option 3. Profiles already removed from consideration are listed by taking option 2. (You’ll find that IBM has already primed this list with most of the IBM-supplied profiles.) Once you take menu option 4 to set the number of days, the job QSECIDL1 is scheduled in the basic job scheduler to run just after midnight. This daily job will evaluate all profiles, minus the ones specified in menu option 2 and disables them based first by examining the Last used date (not the last sign-on date), then Creation date, and finally the Restore date of the profile. If you have no tools in place to “age” profiles—that is, disable them after a period of inactivity, this is a good (and free!) tool to get you started. However, before implementing, you may want to do some analysis of profiles that will be disabled or be prepared the day after starting up this utility to re-enable profiles that shouldn’t be disabled.

Options 5 and 6 allow you to specify profiles to disable/re-enable on a specified schedule. For example, perhaps you have vendors that you know should be accessing the system only Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. You can use this feature to disable the profiles when they shouldn’t be on the system and enable them just prior to working hours.

Figure 3: Use the Change Activation Schedule Entry command.

Options 7 and 8 allow you to disable or delete a profile on a specific date. For example, if you create a profile and you know it’s going to be used only for the next week, you can take menu option 8 and specify to delete or disable the profile on a specific date. This is similar function to what was added to the Create/Change User Profile (CRT/CHGUSRPRF) commands several releases ago except that the commands only support disabling (not deleting) profiles. Also, the CRT/CHGUSRPRF commands are slightly more flexible in that you can specify that the profile should be disabled on a specific date or after xx days. For example, you can specify to disable the profile in 30 days:

CRTUSRPRF USRPRF(NEWPROFILE) PASSWORD() USREXPDATE(*USREXPITV) USREXPITV(30)

I hesitate to even mention these next options, but someone might scroll down on the SECTOOLS menu and find them, so I’ll go ahead and explain their function. At the end of this menu are option 60, Configure system security, and option 61, Revoke public authority to objects. Do not run these options! If you do, I can say with 100 percent certainty that something will break. The better approach is to discover what would be set and consider setting them manually, but do not run the programs as shipped by IBM. Rather, run the Retrieve CL Source (RTVCLSRC) command against QSYS/QSECCFGS to determine what settings are changed by option 60 and against QSYS/QSECRVKP to determine what commands will be set to *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE. This information can also be found in Appendix G of the IBM i Security Reference manual. Use this information as guidelines for what to secure. But always—always—determine what will break prior to securing commands or changing system values so that you can make an informed decision on whether or not to make the change.

Option 62, Check object integrity, is an option (or the command CHKOBJITG) that should be run periodically. Think of it as a self-check for the operating system. It will verify the signature of operating system objects, their ownership, object state, and more. It can consume resources, however, so I’d run it in a batch job and at a low priority.

Summary

I hope you’ve found it helpful to know what commands, reports, and utilities are available to you to help you gain a basic understanding of your security configuration. I think this is an important step; without this basic understanding, it will be difficult to know what areas of the system need to be addressed.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online