There are still many organizations whose system is not running at the recommended value of QSECURITY level 40 (or 50.)

Editor's Note: This article is excerpted from chapter 3 of the security book, Mastering IBM i Security, by Carol Woodbury.

This excerpt has two sections—one specific to moving from QSECURITY level 30 to level 40 and the other dedicated to moving from QSECURITY level 20 to 40. Regardless of whether the system is at 20 or 30, you must determine whether any programs on the system are violating the rules of level 40, so that’s where I’m going to start.

Moving from QSECURITY Level 30 to 40

At security level 40, the operating system prevents certain actions from being taken. Examples include calling an operating system program directly, accessing an internal control block, and using a job description that names a user profile in which the caller doesn’t have authority to the named profile. The good news is that, while not prevented at security level 20 or 30, these actions are logged into the audit journal as AF (authority failure) entries. This allows us to determine whether there are any issues prior to going to level 40. If you like to live on the wild side, you can most certainly move QSECURITY to 40 and IPL without doing any investigation! But should you run into issues, it’s a hard stop. In other words, your program will fail with a function check, and there’s no getting around the error. You must fix it to continue—that, or IPL back to level 30. I prefer to be a bit more cautious, especially when it comes to production systems, so I always check the audit journal prior to the IPL.

Audit to Determine Whether There Are Issues Prior to Moving to Level 40

Determining whether there are issues that need to be resolved prior to going to level 40 is quite easy. It’s a matter of adding *AUTFAIL and *PGMFAIL to the QAUDLVL system value and making sure *AUDLVL has been specified in QAUDCTL. Then it’s simply a matter of looking for AF audit journal entries. But not all AF entries. Believe it or not, we don’t care if there are AF subtype A entries. Those failures indicate someone didn’t have authority to an object. Nor do we care about AF subtype K entries. Those failures indicate the profile attempting an action didn’t have the required special authority. For this investigation, we are only interested in the subtypes that are specific to level 40. (The subtype is the first character of the entry-specific part of the AF audit journal entry.) The subtypes we need to look for are C, D, J, R, and S. All of these indicate actions that will cause a failure at level 40.

Examining the audit journal for these entries isn’t hard. If you’re using Copy Audit Journal Entries (CPYAUDJRNE), your commands will look like this:

CPYAUDJRNE ENTTYP(AF) JRNRCV(*CURCHAIN)

STRSQL

SELECT AFTSTP, AFJOB, AFUSER, AFNBR, AFPGM, AFPGMLIB, AFUSPF, AFVIOL, AFONAM, AFOLIB, AFOTYP, AFINST FROM qtemp/qauditaf WHERE AFVIOL in (‘C’,’D’,’J’,’R’,’S’);

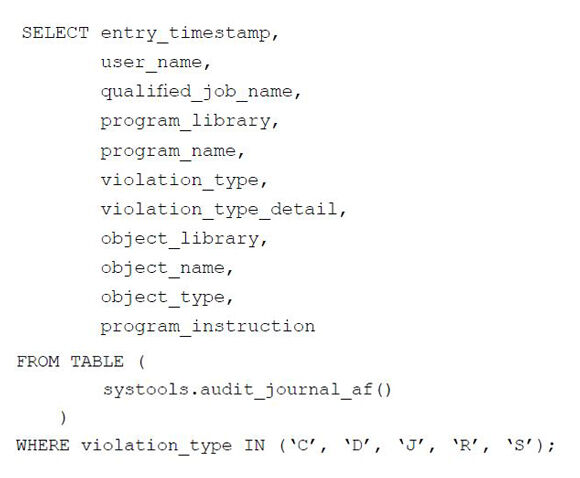

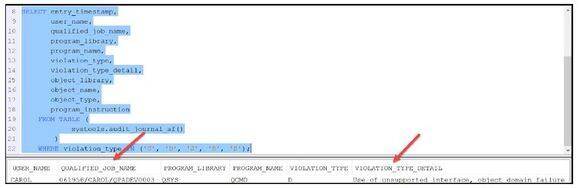

But I prefer a more modern approach. AF is one of the types provided as an SQL table function, so I recommend that you open up ACS, click on Run SQL Scripts, and run this:

Note that I’ve included two fields that are not available when using the CPYAUDJRNE method: qualified_job_name and violation_type_detail. I find the latter to be very useful when explaining these entries to my clients. I think you’ll find them useful too. See Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Some fields are available using the SQL table but not CPYAUDJRNE.

Domain Failures

The entries I typically find at my clients are D (domain failures) and more often, J (job description use). If you have any domain failures, the program name and library in the D audit journal entry identify the program running at the time of the failure. The object name is the object being accessed, and if there’s an instruction number, that’s the statement number in the program where the object is accessed. It’s usually that an operating system program is being called rather than a command or API. One of my clients had domain failures because they were directly calling the program that’s called by the SIGNOFF command rather than calling the command itself. Why the original programmer coded it this way is beyond me, but it was an easy fix, as most domain failures are.

I have not seen an application that doesn’t run at QSECURITY level 40 for many, many years. However, you may see some AF-D entries listed for them. Some vendors still take a different code path at the lower security levels than at level 40 or 50. If you discover entries for vendor products, don’t assume there’s an issue. A quick call to the vendor will verify that their application does run at level 40 and you can ignore those audit journal entries.

I will often find no audit journal entries and wonder whether my SQL is correct or I’m missing something. If I need to test my method, I’ll force an AF-D entry. That’s easily done by attempting to call an operating system program. Since I’m familiar with it, I attempt to directly call the program that’s called by the Create User Profile (CRTUSRPRF) command. Simply running the following from a command line will cause an AF-D entry to be generated:

CALL QSYUP

It’s a quick and easy way to make sure you’ll detect issues if you have any. Most of my clients have no issues, so this is the only entry that shows up in my reports.

User Profiles Specified in a Job Description

J entries, as I said, indicate the use of a job description that specifies a user profile. Most of the time, job descriptions are created so that the person using the job description is the profile under which the job runs. But the USER parameter can be specified with the name of a user profile. In this case, when the job description is used, the job runs as the profile specified in the USER parameter. The problem with this and the exposure it causes at QSECURITY levels 20 and 30 is that, at these levels, the user only needs authority to the job description, not the user profile named in the job description. Therefore, if you have a job description that names a powerful profile, people can use the job description and elevate their authority. Vendors will often ship job descriptions that name powerful profiles (that is, profiles that have all special authorities) with their products. If those job descriptions are not *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE, they’re an exposure if your system’s not at QSECURITY level 40 or 50. (At levels 40 and 50, attempting to use a job description that names a user profile to which you don’t have *USE authority will fail.) But it’s not just vendors that do this. I’ve also seen client-created job descriptions that specify a profile.

So what do you do if you encounter J entries? Part of your challenge will be to determine which job description caused the audit entry. One would think that would be in the audit journal entry, but it’s not. What’s listed is the user profile named in the job description. The easiest way to get the list of job descriptions that specify the user profile in the AF-J entry is to use the QSYS2.JOB_DESCRIPTION IBM i Service as follows (obviously substituting the profile named in the audit journal entry for XXXX).

SELECT job_description_library, job_description, authorization_name

FROM QSYS2.JOB_DESCRIPTION_INFO

WHERE authorization_name = ‘XXXX’;

If it’s not obvious which job description is causing the issue (often looking at the job description’s last used date will make it obvious), you can start Authority Collection on the job descriptions to determine who and which processes are using them. But I’ve never had to go to that length to figure it out.

What do you do once you’ve identified the offending job descriptions? I’ve found that, in most cases, either the job description no longer has to be used or it’s preferred that the job run as the actual user, so the USER parameter is changed back to the default of *RQD or it’s switched out to another job description. The absolute last resort that I use to resolve this issue is to set the profile to *PUBLIC *USE. It’s the last resort because it allows the profile to be specified, not just in job descriptions but also on a Submit Job (SBMJOB) command. And I would take this step only if the profile had no special authorities and did not own the application (or anything else important).

I have not seen an application or system that cannot be moved to QSECURITY level 40 (or 50) in ages. Most of my clients have had no changes to make and can IPL to level 40 without issue. Obviously, you’ll want to audit to make sure that’s the case for you, but even if you discover something that needs to be changed, it’s unlikely that it will be a major change.

Next time: Moving from QSECURITY Level 20 to 40. Want to learn more? You can pick up Carol Woodbury's book, Mastering IBM i Security, at the MC Press Bookstore Today!

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online