Programming Style Issues

Many books and articles have covered the subject of programming with style. RPG hasn’t played much of a role in style discussions, due mainly to the fixed-format nature of its calculations. Now, with free format, RPG programmers can, and should, pay attention to matters of style. With that goal in mind, here are some points to remember as you get started coding in free-format RPG IV.

Mixing Formats

Today’s RPG IV language is flexible enough to let you code in any of three basic formats that I will call original, extended Factor 2, and free format. The original format (still available) includes support for level break, one condition indicator, Factor 1, Operation code, Factor 2, Result, Result definition, and three resulting indicator areas. Many fixed-format operations require this format. It requires a C in position 6, and line comments (denoted by *) start in position 7.

Extended Factor 2 came into being with the advent of RPG IV, and IBM has enhanced it over the years. It is really a semi–free-format option that has gained a wide margin of acceptance. This format still has level break and conditional indicator capability, although programmers seldom use these options today. The operation codes that exploit the extended Factor 2 format are limited to CallP, Dou, Dow, Eval, For, If/Elseif, Return (in a subprocedure), and Select/When.

Extended Factor 2 operations still require a C in position 6, comments (*) starting in position 7, and Factor 1 in positions 13–26. This format mixes easily with RPG’s original fixed format.

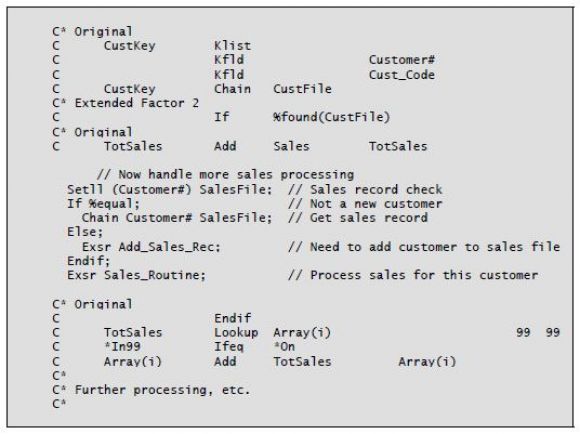

You can combine fixed-format (both original and extended Factor 2) and free-format calculations within the same program, but the resulting code, although perfectly functional, may not look very good or be maintained easily by other programmers. Listing 4-6 shows a program segment that mixes use of RPG’s original format, the extended Factor 2 format, and free format in its calculations. As you can see, the result is a jumble of various types of source code that will take a maintenance programmer a while to make sense of.

Listing 4-6: Examples of mixing the original format, extended Factor 2, and free format

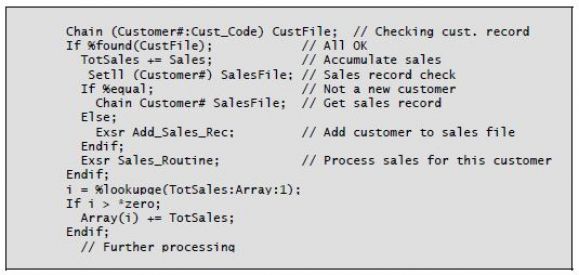

Now take a look at Listing 4-7. This version of the code shows how writing all your calculations in free format can improve the readability of your programs. The flow of control is clear, ample comments explain each key operation, and the code will be easier for another programmer to understand and modify when the need arises to do so.

Listing 4-7: Sample calculations using free format only

As you update old programs and write free-format code to your level of comfort, it is likely you will have some programs that mix fixed and free format. When considering free format, though, you must eventually decide whether to continue mixing formats or to adopt free format for all your calculations. I believe that the authors of the free-format RPG IV compiler anticipated this decision point and provided ample functionality entirely in free format. In effect, they wrote a compiler within a compiler. They could have separated the free-format capability from the other formats and come up with an entirely new language, but they didn’t—at least so far.

While we are on the subject of the “old” and the “new,” let me note that companies that are still converting their RPG/400 programs to RPG IV using IBM’s CVTRPGSRC (Convert RPG Source) command do not have an option for free format. However, a third-party vendor, Linoma Software, includes a free- format option in its program-conversion offerings. IBM’s Rational® Developer for i (RDi) software has a conversion utility that converts RPG/400 to free-format RPG IV. Neither of the conversion programs provides a complete conversion.

There are several fixed-format operations that do not convert easily, so converted programs may have a mixture of fixed and free-format statements.

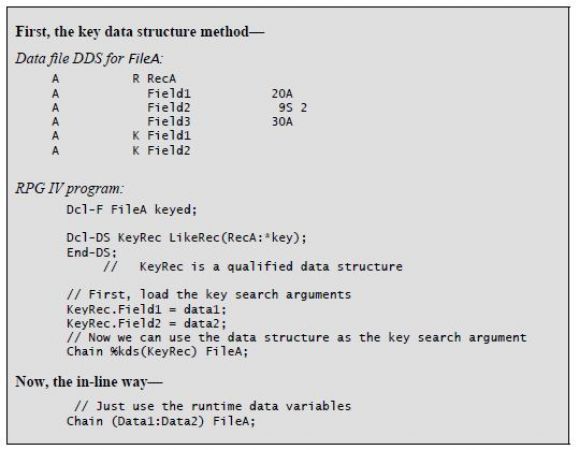

Keyed Access

Keeping your code totally free of any fixed-format calculations brings some other coding factors into play. Without Klist and Kfld operations, for example, you must use either a data structure (with the *Key option) and the %Kds built-in function (for Chain and Setxx operations) or in-line key arguments. I prefer to use in-line arguments when there are only a few arguments but use the %Kds function grudgingly when there are many arguments. That’s because with the %Kds method, you need to load the data structure subfields before using Chain or Setxx, but with the in-line method no additional lines are needed.

Listing 4-8 illustrates each of these methods. (For the inline example, assume the same file (FileA) and record (RecA) as used in the data structure example.)

Listing 4-8: Using the key data structure method and in-line key list parameters

Named Indicators

The ability to name an indicator came to RPG IV around V5R1 without much ado. I saw this enhancement as a great leap forward in the modernization of the RPG language. The indicator data type puts RPG on par with other modern languages that feature similar data types, such as C, Cobol, Java, and even CL. RPG IV’s indicator data type is equivalent to a variable defined in CL as *LGL (logical). Other languages call this primitive a Boolean, meaning that 0 (zero) and 1 (one) are its only permitted values. RPG IV’s named indicators have all the same attributes as the numbered ones, except that they can’t be used in fixed-format operations that set a resulting indicator.

Named indicators can add value to your programs, but only if you name them well. Naming an indicator Flag22 is no better than using a numbered indicator, but a name such as Invalid_acct_num can make your program easier to read and maintain.

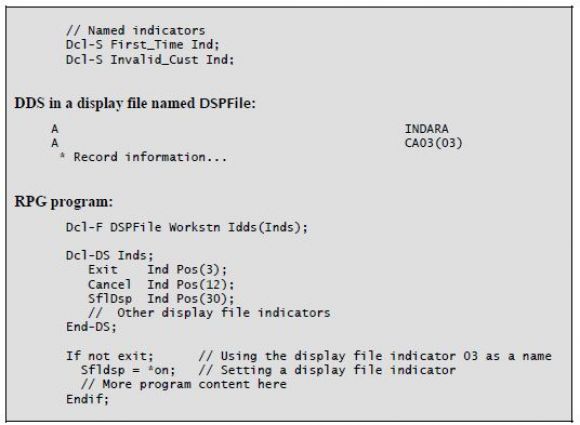

Naming File Indicators

In addition to naming “general-purpose” indicators, you can name the indicators associated with a file, especially a display file. Using good names for conditioning or response indicators is sometimes difficult. Keep reminding yourself that longer names are okay.

To name a file indicator, first specify the file-level keyword INDARA in the file’s DDS. Doing so causes a separate indicator area to be generated for the file. (Our friends coding in Cobol have used this technique for a long time, but we in RPG haven’t needed it.) Then, in the RPG IV program, specify keyword INDDS (indicator data structure) on the file declaration, providing the name of a data structure as the keyword value.

Next, code the named data structure in the data structure declaration. Each subfield entry matches an indicator used in the file. Here is where you specify the name of the indicator. For internal type, enter an n and either “from” and “to” numbers matching the indicator number or, in the keyword area, keyword Overlay(parm1:parm2), where parm1 is the data structure name and parm2 is the indicator number. If you “double-use” indicators (in different formats), simply make up another subfield using a different name and the same indicator number. Just be sure you’re careful in this practice.

One more thing. When using the indicator data structure, the RPG program no longer knows the file indicators by their numbers, only by their names. The numbered indicators are no longer used for the file.

Another indicator-related change that IBM made to RPG IV is the ability to name the overflow indicator used on printer files. Specify a defined named indicator on the OFLIND (Overflow indicator) keyword of the printer file’s file description. This named indicator is set on automatically when a print line is on or after the specified overflow line. The named indicator must be set off after overflow processing to avoid invalid overflow processing.

Note that there is one situation in which you must continue to use a two-letter indicator: You must still use the LR indicator to terminate a program.

Listing 4-9 shows examples of naming indicators.

Listing 4-9: Examples of named indicators and using an indicator data structure

Summing Up

Free-format RPG IV is no longer new; however, IBM has enhanced the language with every release since it became available in 2001. Free-format RPG coding is quite different from the original RPG calculation specifications, but it is not too dissimilar to the extended Factor 2 style of coding. Free format’s coding rules are easy to remember: operation code, then Factor 1, then Factor 2. Ending a statement with a semicolon is probably the thing you’re most likely to forget.

When you code in free format, you will find built-in functions essential.

Many operation codes of the fixed-format variety are available only as built-in functions in free-format RPG IV.

With free format, you are free to code lines any which way you like, and the compiler won’t care. You’ll find that coding free format with style makes all the difference in the world. Other free-form languages (such as C, Java, Pascal, and PL/1) have crossed this figurative “bridge” already, and we can learn from their style. To make our programs better in free format, we must decide to follow style guidelines, such as indenting. We must also use comments—liberally. The addition of named indicators gives free-format RPG IV programmers the ability to code RPG IV like other modern programming languages.

You can still code RPG IV using the original calculation format, nearly the same way the language was coded in the 1960s. Or, you can decide to try this new, free-format approach using some of the style methods suggested in this book. In the next several chapters, I show you how to code common programming requirements in free-format RPG IV. Then we’ll examine some special conversion situations and look at four sample programs that illustrate the new RPG IV free-format style of coding.

More of Free-Format RPG IV is coming soon in an upcoming issue of MC RPG Developer. Can't wait? You can pick up Jim Martin's book, Free-Format RPG IV: Third Edition at the MC Press Bookstore Today!

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online