IBM's announcement of a partnership with 3COM to port its Voice over IP (VOIP) server to the System i has brought a lot of attention to this technology. VOIP seems like it should be a simple concept, right? Take packets of voice data, digitize them, and send them to another IP address. Let that IP address then play the data. Nothing to it, right?

Well, as it turns out there is a lot more to it, with issues that range from the 50,000-foot level of interaction with the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) to the bare-metal detail of UDP traffic over firewalls. This article is for iTechnology Manager, whose focus is more on the business of IT rather than the nuts and bolts. By the time I'm done, you'll see not only why VOIP may actually be the trigger to the next step in the evolution of enterprise application software, but also how moving this technology to the iSeries is the next step in the evolution of the platform.

In this article, I'll explain the technology and the alphabet soup of acronyms surrounding it, from SIP to STUN. I'll then detail the many features that VOIP provides for the enterprise. Finally, I'll address some of the reasons why the IBM/3COM partnership looks to be very successful.

You Know It's Coming—The History Lesson

Be honest. You knew I'd give you a history section. However, this one will be short, since the history of VOIP itself is relatively short and, more importantly, relatively stable. VOIP started roughly back in 1995 or so, and the first real product was a "soft phone" (a software program that runs on your PC and uses a soundcard and a microphone to emulate a phone) from a company called Vocaltec in 1996. Vocaltec is still in business and has since become a provider of industrial-strength VOIP equipment targeted primarily at carriers and service providers.

VOIP Protocols

The only fundamental change in the industry in the last 10 years has been the standardization of the VOIP protocols. Several protocols are still in place. The oldest is probably the H.323 standard, developed by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). While the ITU is the official standards body for H.323, if you really want more information, I'd suggest starting at the OpenH323 Web site. The other major player is Megaco, or H.248 (another ITU standard). Megaco stands for Media Gateway Control and is designed for both voice and video conferencing. Without going into a lot of detail, the primary difference between Megaco and H.323 is that Megaco requires a smart network, while H.323 protocol can easily be routed over the Internet. It comes down to where the device control is located: in the device or in the network. For a number of reasons, including reliability of emergency services, Megaco has advocates among public carriers. However, the majority of enterprise-level providers have pretty much centralized on the H.323 approach of intelligent devices.

There are other protocols, but the only real contender has been Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), which in fact has become the predominant player in the industry. SIP is also an intelligent device protocol, in which a SIP-enabled endpoint device communicates with another such device over an IP network. Most companies that provide VOIP services support SIP either exclusively or in addition to H.323 and Megaco protocols. From this point forward, I'll assume you will be using SIP, although most of the points are germane to H.323 and to a lesser extent Megaco.

Features of VOIP

Unlike the protocol, the feature set of VOIP has changed dramatically. The original use for VOIP was to carry expensive long-distance telephone conversations over inexpensive Internet connections. There are still VOIP service providers that will allow you to make free long-distance calls after listening to a brief advertising pitch. However, as the various media communications products continue to converge, an abundance of features have emerged, with new ones being added every day it seems.

For example, "find and follow" allows you to get your phone calls on your same number regardless of where you are in the world. If you have connectivity to your IP network, you can get phone calls. Unified messaging allows you to send voice, video, and email using the same connection. Multicast can easily broadcast information to multiple people, while conferencing lets you to pull multiple people into a single session. Because all of this is digital, it means that you can do it through your workstation: Drag and drop a person onto a conference call, and point and click to send a voicemail. How about the ability for someone to point and click to dial an information or support line directly from your corporate Web site?

A second area of functionality surrounds collaboration. I touched on conferencing, but when combined with basic collaboration software features like presence, it becomes very easy to find people and add them to the conference call. A phone call can easily be turned into a conference call and then into a video conference as requirements change. People can tune in or out as needed. Information can be shared either via whiteboards or file sharing.

But perhaps the most exciting area of the entire VOIP process is the integration into your enterprise software. Many of the features of VOIP can be had through third-party services (products like GoToMeeting come to mind). But what about the ability to see a problem in a customer order and simply point and click to call that customer? It's even more impressive if you already have someone else on the line who can fix the problem: You identify the problem, call the person who can fix it, and then conference in the customer. All of this just using your mouse. This is where the future of VOIP will start to really come into play.

VOIP Implementation

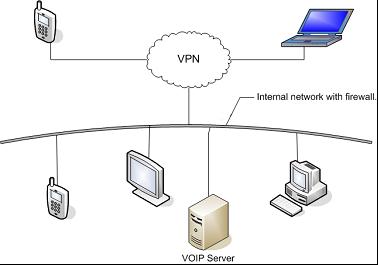

So let's look at what is required to implement VOIP. There are really two variants of VOIP architecture: the enterprise "island" and the private-to-public connection. The enterprise island (as depicted in Figure 1) involves a number of devices that communicate with one another using a VOIP server to provide additional functions (technically, if you have two SIP-enabled devices on the same network and you know the IP addresses of each device, you don't need a server, but you also lose many of the neat features).

Figure 1: This basic VOIP setup allows people on the network (including VPN) to communicate. (Click images to enlarge.)

The coolest part about this is that people on the road get all the features of the VOIP server as soon as they connect to the network via VPN. It's an opportunity to really keep your employees connected.

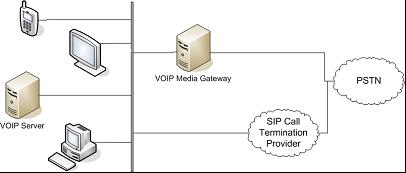

However, since the whole world is not VOIP-capable, you can't deploy an enterprise-wide VOIP solution without connectivity to the traditional PSTN. This is done via one of the configurations shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The options for SIP connectivity to the PSTN are a gateway or a service provider.

The options are pretty simple. You can have your own in-house gateway to convert SIP to the sort of signals that came from the older-style PBXs that the PSTN can understand. The other option is to contract with a SIP call termination service provider, who will in effect do the same thing, only at its site. You have a number of factors to weigh when making this decision, from reliability and control with an in-house solution to the ability to choose between various vendors for the outside option. An interesting side effect of choosing a service provider means that the service provider doesn't need to be geographically close; you can transmit your IP traffic to it from anywhere in the world and then use its local number. Thus, even if you're located in Bar Nunn, Wyoming, you can make it look as though your office is physically in New York or London or Tokyo.

There is a legal ramification here: Since VOIP networks aren't capable of true emergency phone services (e.g., 911), you may want to check what liability you would have if you switched to a pure VOIP system in your enterprise. You may need some sort of PSTN backup if only for emergencies.

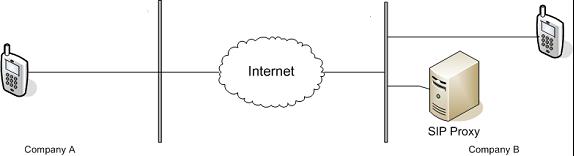

The final configuration is the one currently least likely to be used, even though it's often shown in discussions of the topic. Here, the Internet is used as a bridge between SIP-enabled phones on completely different networks, both behind firewalls. An example might be a student calling in from home to a university network. In the business world, it might be a customer connecting to a vendor's VOIP network.

Figure 3: This is the connection between islands, where each IP phone is behind a firewall.

In Figure 3, I've simplified the network considerably to basically just one IP phone calling another. In this case, Company A and Company B have their own private networks behind firewalls and they are not connected via VPN. Typically, these days each company would use Network Address Translation (NAT) to convert an external IP address to the internal IP addresses used by the actual devices. However, VOIP requires direct UDP traffic from one device to the other. Since UDP traffic is not handled by the NAT router, we need another way to perform the routing. We do this via a technique known as Simple Transversal of UDP through NAT (STUN). STUN is facilitated by having a server box at the destination site that can make the information available that the NAT normally hides. This is the SIP proxy box shown in Figure 3. (I have some concern, though, that a SIP proxy, since it makes the internal addresses known to the outside world, could conceivably be a point of weakness to the network.)

As I said, such a configuration is not the norm; today, if you want features like video conferencing with another company, you'll typically have a VPN connection to that company. However, as these sorts of services become more common, I think you'll see more crossing of network boundaries. For example, it could be very helpful for me to be able to view a directory of people at a client site and see who is available and even include them in on a conference call. If nothing else, this sort of directory access could replace the voicemail menu most companies have nowadays.

So Why the System i?

OK, out of the technical minutiae and back to the world of business. Why would you want to host your VOIP server on the System i? There are a number of reasons, beginning with the simplest one of cost. Because you don't need dedicated hardware, you immediately save that cost. But the cost savings argument is even more powerful when you take into account the System i's virtualization capabilities. Let's say you typically need only 120 users at any one time, except for once a quarter when you give a corporate conference call that needs 600 users. With dedicated VOIP equipment, you would have to buy the capacity for all 600 users, even if 80% of that capacity went unused most of the year. By placing your VOIP in a System i partition, you can simply "borrow" some resources from another partition when that big conference call comes up (or even kick in the Capacity On Demand feature to get a little extra oomph). This may be the first application that really shows off the incredible flexibility of the System i as opposed to any other platform. A single box that can easily shift resources from one enterprise system to another—that's the kind of thing no other vendor can compete with.

Combine this with the reliability of the box. How often do you want your phone system to go down? As often as a Windows box or as often as a System i? I think it's reasonable to want to run something mission-critical on the most reliable platform in your company.

But beyond those obvious reasons, there's yet one more reason that's perhaps less apparent. I mentioned collaboration a little earlier, and this is where many people think the real power of VOIP will come into play. As you begin to integrate your VOIP systems with your business processes, you will start to see immediate gains in productivity, but only if your VOIP systems have access to your enterprise data and enterprise applications. As you integrate more of your business processes, access to both data and programs will be a cornerstone of raising productivity. Delayed deliveries can immediately bring up lists of affected customers who can in turn be sent an email or even a voicemail outlining possible alternatives. A couple of clicks can create a conference call between you, the vendor, and the recipient of a drop-ship order. But this requires a system with transparent access from the VOIP system to the enterprise, and the System i is ideal for such integration.

And Finally, Why 3COM?

While I don't have enough experience to be able to recommend one vendor over another for any VOIP functions, I can at least give you IBM's reasoning behind choosing 3COM as its partner, and you can use that in your own deliberations.

First, IBM liked 3COM's focus on integration. If the "i" in System i stands for anything, even unofficially, it stands for integration. The ability to run the entire product in a System i partition was a key factor in partnering with 3COM. The second reason IBM chose 3COM was its dedication to industry standards. While Microsoft continues to move toward more and more proprietary technologies, 3COM has instead embraced the SIP protocol fully, and that certainly warmed the hearts of the IBM strategists. Finally, and to me most importantly, 3COM is focused on the mid-market segment. Those core companies that make up the SMB market space are 3COM's bread and butter, and the fact that IBM chose to partner with 3COM is simply one more reason for me to be optimistic about IBM's commitment to the SMBs (and the ISVs that serve them, like me).

Conclusions

VOIP has been around for a while already. It's a powerful technology that can provide many features to any company. Integrated with your enterprise database and business functions, suddenly VOIP leaps ahead to a whole new level of functionality. Integrate those two systems—VOIP and enterprise business suite—on one box that can share resources among them as needed, and you suddenly have what may be the first "killer integrated system."

Joe Pluta is the founder and chief architect of Pluta Brothers Design, Inc. He has been working in the field since the late 1970s and has made a career of extending the IBM midrange, starting back in the days of the IBM System/3. Joe has used WebSphere extensively, especially as the base for PSC/400, the only product that can move your legacy systems to the Web using simple green-screen commands. Joe is also the author of E-Deployment: The Fastest Path to the Web, Eclipse: Step by Step, and WDSC: Step by Step. He will be speaking at Local User Group meetings around the country in April, May, and June; you can reach him at

More than ever, there is a demand for IT to deliver innovation. Your IBM i has been an essential part of your business operations for years. However, your organization may struggle to maintain the current system and implement new projects. The thousands of customers we've worked with and surveyed state that expectations regarding the digital footprint and vision of the company are not aligned with the current IT environment.

More than ever, there is a demand for IT to deliver innovation. Your IBM i has been an essential part of your business operations for years. However, your organization may struggle to maintain the current system and implement new projects. The thousands of customers we've worked with and surveyed state that expectations regarding the digital footprint and vision of the company are not aligned with the current IT environment. TRY the one package that solves all your document design and printing challenges on all your platforms. Produce bar code labels, electronic forms, ad hoc reports, and RFID tags – without programming! MarkMagic is the only document design and print solution that combines report writing, WYSIWYG label and forms design, and conditional printing in one integrated product. Make sure your data survives when catastrophe hits. Request your trial now! Request Now.

TRY the one package that solves all your document design and printing challenges on all your platforms. Produce bar code labels, electronic forms, ad hoc reports, and RFID tags – without programming! MarkMagic is the only document design and print solution that combines report writing, WYSIWYG label and forms design, and conditional printing in one integrated product. Make sure your data survives when catastrophe hits. Request your trial now! Request Now. Forms of ransomware has been around for over 30 years, and with more and more organizations suffering attacks each year, it continues to endure. What has made ransomware such a durable threat and what is the best way to combat it? In order to prevent ransomware, organizations must first understand how it works.

Forms of ransomware has been around for over 30 years, and with more and more organizations suffering attacks each year, it continues to endure. What has made ransomware such a durable threat and what is the best way to combat it? In order to prevent ransomware, organizations must first understand how it works. Disaster protection is vital to every business. Yet, it often consists of patched together procedures that are prone to error. From automatic backups to data encryption to media management, Robot automates the routine (yet often complex) tasks of iSeries backup and recovery, saving you time and money and making the process safer and more reliable. Automate your backups with the Robot Backup and Recovery Solution. Key features include:

Disaster protection is vital to every business. Yet, it often consists of patched together procedures that are prone to error. From automatic backups to data encryption to media management, Robot automates the routine (yet often complex) tasks of iSeries backup and recovery, saving you time and money and making the process safer and more reliable. Automate your backups with the Robot Backup and Recovery Solution. Key features include: Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online