Carol answers the questions you’ve been asking about securing IBM i commands.

Every once in a while, I get asked a question that spurs on an idea for an article. That’s what happened this week when I was asked whether one had to secure proxy commands. That made me realize that I hadn’t written about the security considerations one needs to make regarding Command Language (CL) commands, so I decided to make that the focus of this month’s column.

Which Commands Should Be Set to *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE?

I am often asked for my list of commands that should be set to *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE. When asked for the list I reply, “It depends,” which is typically met with a groan. But I must respond in that manner because which commands need special attention depends on the role of the system and the security policy of the organization. For example, it’s pretty obvious that one wouldn’t set the commands that create programs to be *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE if the system is used for code development. However, in some organizations, compiling in production is strictly forbidden, so in that case, securing the CRTxxxPGM commands is totally appropriate. But there are other organizations where, as part of the normal code promotion process, the source is copied from development to production and compiled on that system. In this case, the CRTxxxPGM commands may be set to *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE, but the profile under which the promotion process runs has to be authorized to the commands.

IBM does some of the work for us. Many commands ship with the system already set to *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE. For the list of commands, see the IBM i Security Reference manual, Appendix C. This appendix also lists whether QPGMR, QSYSOPR, QSRV, and QSRVBAS are granted a private authority to the command.

Some people ask why I don’t secure commands such as Create User Profile (CRTUSRPRF.) I’ve seen auditors get hung up on this as well. When I teach my “Auditing the IBM” class, I try to help the auditors understand that risk is reduced much more if the focus is on which profiles have been assigned specific special authorities rather than focusing on the *PUBLIC authority of commands such as CRTUSRPRF. Appendix D in the IBM i Security Reference manual lists the authorities required to run each CL command as well as the special authority requirements.

The commands I tend to focus on are those commands that don’t require a special authority and aren’t already shipped by IBM as *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE. These commands tend to be commands such as Create Library (CRTLIB), Create Directory (CRTDIR), Make a Directory (MKDIR), and Add Server Authentication Entry (ADDSVRAUTE). When sound object-level security hasn’t been implemented, I start to focus on commands such as Start Data File Utility (STRDFU), Update Data (UPDDTA), Work with Queries (WRKQRY), Run Query (RUNQRY), and Start SQL (STRSQL). These are all commands that can allow someone to create a container (a library or a directory) that could (1) potentially hide dangerous code, or (2) hold copies of production data, or (3) pose risk to inappropriate viewing or modification of production data.

What’s a Proxy Command Anyway?

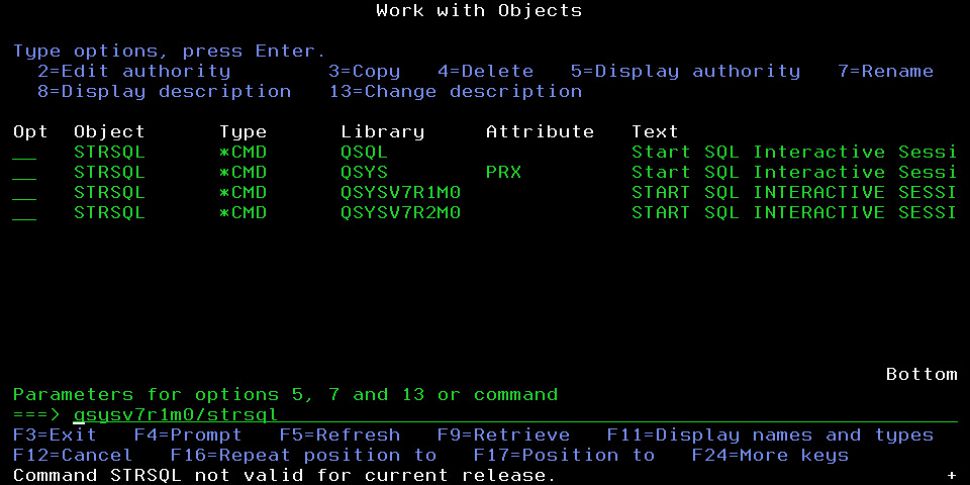

Proxy commands were introduced in V5R4. Proxy commands are basically a shortcut to an actual command. Think of a shortcut on your desktop. The executable that corresponds to the icon is typically not residing on your desktop; it’s usually in a subdirectory elsewhere on your workstation. When you click on the icon, the executable is launched. That’s basically what happens when a proxy command is run. The proxy command doesn’t have source associated with it. What runs is the underlying command that the proxy is pointing to, not the proxy command. In the screenshot below, the attribute PRX indicates that there’s a proxy command for STRSQL in library QSYS, but the actual command is in QSQL.

To run a proxy command, you have to have authority to both the proxy command and the actual command. While you can secure a proxy command, it makes more sense to focus on the actual command and secure that, especially if it’s a command such as STRSQL where, no matter what command calls it, you want to make sure the actual STRSQL command is run only by approved users.

Figure 1: Several versions of the STRSQL command exist on the system.

What About Those QSYSVxRyMz Libraries?

As shown in my screenshot, instances of most commands exist in these earlier version libraries. These libraries exist to facilitate creating CL programs that are going to be restored to one of the previous two operating system releases. In my example, my system is running V7R3. Because these libraries are on my system, I can compile a program to be restored and run on a system installed with either V7R2 or V7R1. The good news is that you don’t have to do a thing to secure these commands because they can’t be run on the current version. You can see the error I received when I attempted to run the STRSQL command out of the QSYSV7R1M0 library. Nothing prevents you from setting the authority on these commands to *PUBLIC *EXCLUDE, but it would only serve to prevent someone from compiling a program containing the command.

Got Questions?

Thank you to Steven for asking the question about securing commands this week. My clients and my readers are typically my inspiration for these columns, so don’t be afraid to ask questions! The answer may just appear in a future column.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online