AS/400 security can be a little intimidating. There are so many features and options that it seems impossible to determine how applications will interact with objects. But wait—applications are objects! How will their security attributes affect their access to other objects? What about adopted authority? What happens with TCP/IP? Too many questions. Too much to understand. What about blowing it all off and having a beer?

The good news is this: While there is a lot to know about the AS/400’s security features, you can understand how to configure those features. This article will help you establish a working understanding of object-level security and what paths applications will take when accessing objects. Simply put, object-level security allows you to control not only access to objects but also the type of access users have.

The AS/400 allows four basic types of access to objects. *ALL means you can access anything; *CHANGE lets you change objects; *USE lets you use the object; and finally, *EXCLUDE means you can’t access anything. These can all be applied at the user, group, or authorization-list level.

Why are there so many security features? Good question. I’m sure I don’t know, but I have a guess. The U.S. Department of Defense is (and almost always has been) the single largest purchaser of computer equipment in the world. The U.S. Department of Defense likes security features. It may interest you to know that the AS/400 is the first system with an integrated database to meet the department’s criteria for its C2 level of security. In order to obtain a C2 rating, a system has to meet strict criteria in the areas of access control, user accountability, security auditing, and resource isolation. If you think about it, discretionary resource control and isolation basically mandate object-level security.

Securing the Object

Every object in the system has its own list of authority attributes. This list is, in essence, a description of who can do what with the object. The first item in the list is the object’s owner.

Who owns the object? When the object is first created, the user profile of its creator is the object’s owner. By default, the owner has *ALL authority. That is, the owner can use, change, or delete the object. If the owner’s user profile is deleted, ownership falls to QDFTOWN, the system default. Using the Change Object Owner (CHGOBJOWN) command, you can transfer ownership to another user’s profile or to a group profile. For

example, when I develop an application for my company’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, I change its ownership to the group profile associated with the system’s users. This avoids access control problems. (Security officers, of course, have *ALL authority over all objects.)

Using the Work with Objects (WRKOBJ) command, or the specific object authority commands, you can grant (with the Grant Object Authority [GRTOBJAUT] command), revoke (with the Revoke Object Authority [RVKOBJAUT] command), or modify (with the Edit Object Authority [EDTOBJAUT] command) an object’s specific authorities. By specific authorities, I mean those authorities granted to (or taken away from) a user or group profile to give the profile a specific type of access.

As I stated, there are actually four types of specific authority. The first, *ALL, is fairly obvious. A user or group profile with *ALL authority for an object can do anything with the object. It seems redundant to point out that you should be careful when granting *ALL authority. You’ll understand why when your transaction history file mysteriously disappears.

*CHANGE lets the user or group profile change the object, but this authority means slightly different things for different types of objects. For example, the user can clear, read, or change the records in a database file. But with a program or command object, the user can only use the object. *CHANGE authority does not allow you to delete an object or change any of its security attributes (such as ownership).

Another type of authority that has slightly different effects on different object types is *USE. For a database file, it means you can read records. No deleting, no updating, no writing—just reading. For a program or command object, you can call (execute) it, and that’s it.

The fourth specific authority isn’t really an authority at all. *EXCLUDE means that you can’t do anything at all with the object. You might call this setting the antiauthority.

If you don’t have specific authority to an object—that is, if you’re not a security officer or the object’s owner—your authority reverts to whatever *PUBLIC authority is set. The *PUBLIC authority attribute controls the general public’s access to the object. By general public, I mean the system’s users who aren’t specified in an object’s authority attribute.

Many shops set *PUBLIC to *EXCLUDE as a matter of policy. I can best illustrate the reason with an example. If a user has *USE authority to an object and that authority is revoked, the user may still have *USE authority because the public has it. Using *EXCLUDE prevents accidentally granting people access they shouldn’t have. There is a downside, however: The tighter your system’s security is, the more time you’ll spend administering security on your system. Only you can decide if your time investment is appropriate.

Authority Administration Made Easy

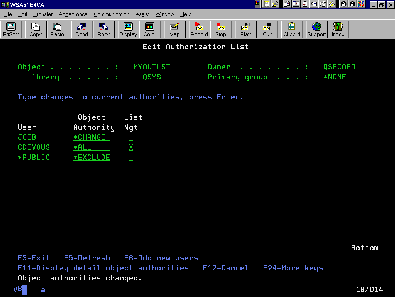

Of course, granting, editing, and revoking authorities by user profile for a system full of objects could take a lot of time, and you have deadlines. What are you supposed to do? Fear not, gentle reader. IBM, the fount of all goodness, has anticipated this need and provided a tool called an authorization list. As shown in Figure 1, an authorization list is simply a list of user profile names with specific authorities for each one. And, you guessed it, an authorization list is also an object.

Naturally, an object can have both specific authorities and an authorization list. Users can even be in both places. This may be redundant, but it is not harmful.

The authorization list commands let you create (Create Authorization List [CRTAUTL]), delete (Delete Authorization List [DLTAUTL]), and edit (Edit Authorization List [EDTAUTL]) authorization lists. The authorization list can then be applied to objects or groups of objects with GRTOBJAUT or WRKOBJ. There is a caveat, however: In a

development environment, using authorization lists can lead to trouble when moving or restoring objects to a system that doesn’t have the authorization list.

Special Authorities

You can also grant special authorities to specific users. While I won’t go into great detail here, users can be granted special types of authority to objects. For example, you can grant a user *SAVSYS special authority. This lets the user back up and restore objects even when she has no authority to the object. See the references at the end of this article for publications that explain the special authorities in detail. My personal favorite is The AS/400 Owner’s Manual by Mike Dawson.

Adopted Authority—You Are What You Execute

IBM also provides a special kind of authority attribute for executable programs called adopted authority. When compiling, you can set the program’s user profile attribute to either *USER or *OWNER. *USER means that the program uses the user’s authority to access objects. *OWNER means that the program uses its owner’s authority to access objects.

How does this help? Once again, I’ll illustrate with an example. Suppose you have a transaction history file that you want users to be able to add transactions to but you don’t want them to be able to, clear the file. If you give the users *CHANGE object authority, they can clear the file. If you give them *USE, they can’t clear the file, but neither can they add records. What do you do?

Well, one thing you can do is write a program to maintain the transaction file and set the program’s user profile attribute to *OWNER. Then you transfer ownership of the program object to a user who does have *CHANGE authority for the transaction file. When the program is executed (no matter by whom), it has *CHANGE access to the transaction file, even if the user running the program has *EXCLUDE (non)authority for the transaction file. This is only one situation in which adopted authority comes in handy. There are many other possible scenarios, too numerous to mention here.

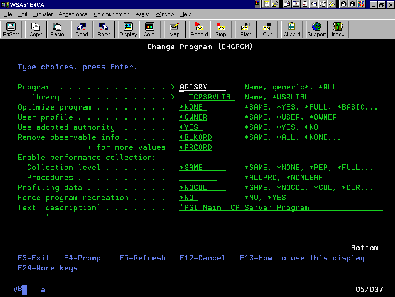

As Figure 2 illustrates, you can use the Change Program (CHGPGM) command to change whether a program uses adopted authority and whether it uses the user profile or its owner’s profile to access objects.

Adopted authority has some risks, however. Programs that use adopted authority (which is the default, by the way) can inherit it from programs higher in the call stack. Go back to my example of the transaction file. Suppose that the maintenance program also serves as an inquiry program by using a program status subroutine to handle authority errors. Users who have *CHANGE authority can use the program to add transactions to the file, and users who have *USE authority can only view the existing entries. The inquiry program is set to use adopted authority. (Remember, this is the default.) A user calls the inquiry program from within another program that has its user profile set to *OWNER, and the owner of the program has *ALL access to the transaction file. Now the user can change the file, when you wanted only to grant him access to use the file. Obviously, this is an extreme example that I have concocted expressly for the purpose of illustrating my point. You can provide adopted authority without realizing it, so be careful!

You can prevent adopted authority by setting the USE adopted authority parameter to *NO (see Figure 2 again). Then, a program will not inherit authority from a program higher in the call stack. In my little example, the user now would not be able to change the transaction file.

Tying It All Together

OK. I’ll get back to the main point. How does object-level security affect your application? Leaving out adopted authority, your application will access objects (or attempt to) with your user’s authority, your user’s group authority, and public authority.

Take a look at another example. Suppose a file’s authority list excludes *PUBLIC, grants *USE to the group profile named GRPPRF, and grants *CHANGE authority to user CHGUSR. You have an inquiry program that opens the file for read (input only) and a maintenance program that opens the file for update (full function). CHGUSR executes the maintenance program that opens the file for update. There’s no problem—CHGUSR has *CHANGE access. CHGUSR can also execute the inquiry program without any difficulty.

Along comes READUSR, who belongs to the group profile GRPPRF, which has *USE authority for the file. READUSR, being a very bad typist, calls the maintenance program. Ka-boom! There’s a program error. Neither READUSR nor GRPPRF has *CHANGE access, which the program needs. READUSR realizes his error and calls the inquiry program. Again, this isn’t a problem. GRPPRF has *USE authority over the file, and READUSR is a member of GRPPRF.

Then, along comes NONUSR, who is not mentioned in the file’s authority attributes. NONUSR is, therefore, a member of *PUBLIC with respect to the file. NONUSR tries to execute the inquiry program. Ka-boom! There’s a program error. NONUSR has no rights. Go back to adopted authority. Change the inquiry program’s USRPRF attribute to *OWNER and change its ownership to READUSR. NONUSR can now execute the inquiry program.

Things External—Those Darn PCs

Now things get a little more complicated. A user running Client Access can use a tool based on ODBC or ActiveX Data Object (ADO) to access objects on the AS/400 as well. In this instance, the level of access is controlled by the user ID under which Client Access connects (which may be different from the user profile the user signs on with). Many shops, by default, set Client Access to connect with a common user ID.

Suppose a user who connects with Client Access has *CHANGE access to a file, or belongs to a group that does, but is prevented from accessing the file because he is restricted to menu access and is not allowed to access any menu that calls a program that changes the file. This is not as uncommon as it may sound. Many installations make users the members of a group with *CHANGE access for all of an application’s database objects and control those users’ access at the menu level.

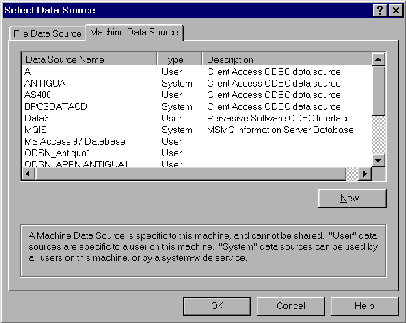

As Figure 3 shows, the user I just mentioned can get at the file and modify it using Microsoft’s Access database management program and the Client Access ODBC driver. This is because ODBC uses the authority of the user profile that Client Access connects with, and, in our example, that profile has *CHANGE authority over the file.

Tread Lightly

This discussion makes one point very clear: Object-level security is not all that complicated, but its interactions can be. You must give careful thought to how and to whom you grant authorities on your systems.

REFERENCES AND RELATED MATERIALS

• An Implementation Guide for AS/400 Security and Auditing: Including C2, Cryptography, Communications, and PC Connectivity, Redbook (GG24-4200-00)

• AS/400 Tips and Tools for Securing Your AS/400 (SC41-3300-01, CD-ROM QBKACF01)

• OS/400 Security—Reference V4R4 (SC41-5302-03, CD-ROM QB3ALC03)

• Security — Basic V4R1 (SC41-5301-00, CD-ROM QB3ALB00)

• The AS/400 Owner’s Manual. Mike Dawson. Carlsbad, CA: MC Publishing Co., 1997

Figure 1: An authorization list is a list of users and their specific authorities.

Figure 2: You can control adopted authority with the CHGPGM screen.

Figure 3: Selecting ODBC data sources can allow users inappropriate access to AS/400 objects.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online