Data queues may be small, but this article shows you how keyed data queues allow you to send big things in little packages.

The previous article on the practical application of data queues showed how you can use a single keyed data queue to allow an arbitrary number of clients to access an arbitrary number of servers. The only constraint was that the message size was limited to the maximum size of a single data queue entry, which is just shy of 64K. That's a pretty significant constraint, but in this article I'll show you how adding just one more data queue completely removes that constraint.

One Queue to Bind Them All

The primary object of any arbitrary-length messaging system is to make sure that the entire message is processed at the same time. As it turns out, it's relatively easy to do that; it just takes a little careful planning and a little timing. Let's start by reviewing my diagram of the single-queue solution:

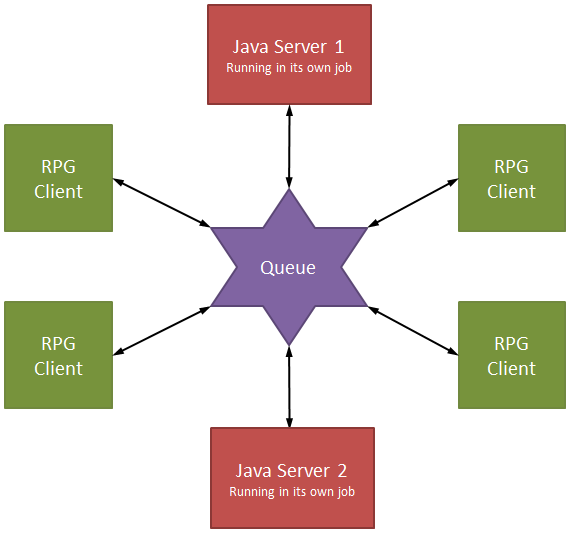

Figure 1: A single keyed data queue can connect as many clients and servers as you need.

The idea is that we put a request on the queue that is then read by the appropriate server. The request looks like this:

Key Value

Server ID

Client Job Number

Request ID

Data

Application-specific Request

The server ID says who will process the request, the client job number is who made the request, and the request ID is an optional identifier in case you have multiple requests (more on that in a moment). The client adds the request to the data queue with the Server ID as the key, and the appropriate server pops the request off. It then responds with a request that looks exactly the same, except the data portion is replaced with the response:

Key Value

Server ID

Client Job Number

Request ID

Data

Application-specific Response

This message is placed on the queue with the Client Job Number as the key. The client is waiting for an entry with that key, and no two clients have the same key. Simple, clean and elegant. As noted, though, the problem is that the message is limited to only 64K. That's enough for simple requests but not nearly enough for many types of services, especially those that return lists of information. So how do we get around that? Well, it's simple: we add another queue for the data!

Keeping Your Bits Together

So the issue is how to handle a request that returns more data than a data queue entry can handle. To do that, I need to revise our diagram a little bit. I'll simplify it down to a single client and server, but I'll add in the request and response. We end up with this:

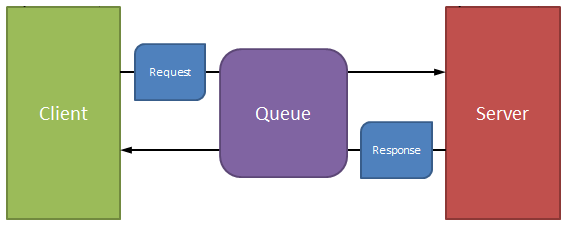

Figure 2: Drilling down into a single communication request shows a simple structure.

The concept is a model of simplicity; the queue has a simple six-character key. The request is placed on the queue with the server ID, and the response is placed on the queue with the client ID (the client job number). No client/server transactions will ever collide. But the request is constrained to that 64K limit; how do we get from that to more than a single piece of data? Enter the second queue!

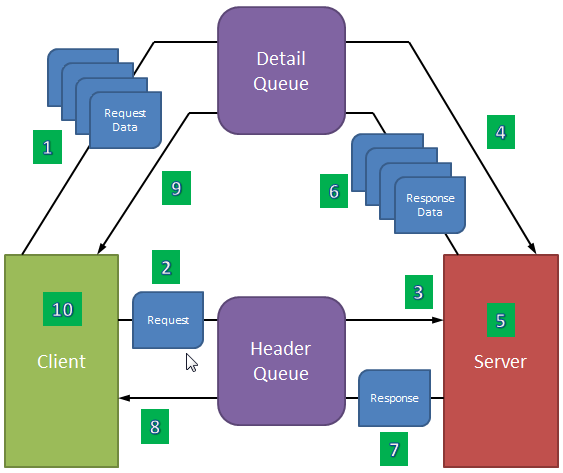

Figure 3: We then add a second queue to handle the variable-length data.

This is the final architecture for an unlimited-length messaging system. The header queue contains one entry each for the request and the response in a transaction. The detail queue can have as many entries per transaction as necessary, which provides an arbitrarily long limit for both request and response. But why a second queue? Why not just send everything on one queue? That's because whoever is reading the queue has no way of knowing whether the transaction data is complete. The sender may have been delayed for processing or some other reason, and the receiver may have gotten ahead of the sender. No data on the queue doesn't mean there is no more data coming, just that it's not there yet; it's very dangerous to use a lack of data as a positive end of message. You could theoretically have an "end of message" transaction, but I prefer not having to look at the data in order to determine the completeness of the message. So basically you want to send all the detail and then the header.

And here's where the timing piece comes in. There are 10 distinct steps in the conversation:

- The client writes all the request data to the detail queue using the data key (which we'll define shortly).

- The client writes the request header to the header queue using the server ID.

- The server reads the request header, which includes the data key.

- The server reads all the request detail data using the data key.

- The server processes the request.

- The server writes all the response detail back to the queue using the data key.

- The server writes the response header to the header queue using the client job number.

- The client reads the response header from the header queue (using the client job number).

- The client reads the response detail using the data key.

- The client processes the response.

It's really important to see how the data is front-loaded. You send all the detail first, and then you send the header. The very act of sending the header indicates to the receiver that the transaction is completely enqueued. It can then read the data until no more data exists; that's the end of the data! There are other techniques, but they all rely on something programmatic: a count in the header, or a special EOF message. A simple programming mistake can easily send those awry. But in this case, the physical act of sending the header after sending the detail ensures the integrity of the message.

I used the term "data key" several times in the list. This data key is what allows this architecture to support multiple clients and multiple servers all running through the same two queues. It prevents interleaving of data on the otherwise FIFO data queue.

The data key is a unique key that defines the message, and it consists of all the key values of the message as defined at the beginning of the article. I used a minimal combination of server ID, client job number, and request ID. In a completely barebones architecture, you could get away with just server ID and client job number, but throwing in the request ID makes it theoretically possible to make several simultaneous requests from the same client to the same server and keep the requests separate. This is important in parallel processing environments, especially if you have multiple instances of the same server. Note: This architecture could also allow you to execute processes on another machine. The server could easily be something that reaches out to a web service or an MQ series queue.

But that's another discussion for another day! For now, just review this architecture and see how it can be used in your environment to allow you to interface your RPG programs with as many servers as you need.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online