Last month, we looked at Microsoft Component Object Model (COM) technology and saw how to use a COM-compliant object like MS Word. This month, we'll take the COM concept a step further and consider when and how to create an ActiveX COM-compliant Dynamic Linked Library (DLL).

DLLs

Have you ever wondered what a DLL is and how it's used? Well, let's talk about DLLs. DLLs are common to Windows operating systems, and the PC doesn't run very well without them. On the other hand, a DLL file will not run by itself, like a program or .exe file does. And everyone's heard of "DLL hell."

A DLL is a collection (or "library") of executable routines. The routines may be run from outside the DLL by another program (or another DLL), but they can't run on their own because they're not ready to interact with the operating system; they rely on the calling program to do that. Routines within a DLL are accessed, or "linked," on the fly, i.e., "dynamically." So, then, a DLL is a library of program routines that are linked dynamically to an external program.

So why are DLLs important? Because DLLs are compiled and linked independently of the applications that use them. That means that the services provided can come from a singular and central place. Further, Windows will only load a single copy of the object code in a DLL into memory, regardless of how many active applications are using it.

How Can You Use DLL Technology?

You use DLLs all the time in the course of running your Windows systems, and you may be able to enhance code reuse and standardization within your enterprise if you create your own DLLs.

Suppose, as a simple example, that you need a way to keep all your PCs and your iSeries in agreement as to the time of day. Having all your PCs synchronized will facilitate certain time-sensitive functions within your company, let's say. So you want to have some mechanism running on each PC in exactly the same way that will access the iSeries and grab the time. This little bit of function will be called from six of your company's custom desktop applications.

This is where the notion of a DLL comes in. You can create a DLL to perform the functions you need, and then tell each of your desktop applications to use the DLL. That way, you only need to have one copy of the code on the PC, and all the applications will share it.

To further illustrate, suppose you expect the requirements for your DLL to change substantially in the future, perhaps to accommodate time zones. Again, you're a winner with a DLL because a DLL can be updated without requiring the applications that use it to be recompiled or relinked. (Remember, the applications access the DLL routines dynamically.)

This is a micro-example of the black-box paradigm, where applications use the centralized services of a code library without knowing or caring how they are provided. The result of this sort of arrangement is standardized functions, reduced maintenance, and reduced overhead. In contrast, consider the case where a DLL is not used. Each application must be fitted with the exact same code and then compiled. When the requirements for the processing change, each application's source code must be modified and recompiled, and the resulting executables must be redistributed to all your PCs.

DLL Drawbacks

On the other hand, some problems can arise as a result of employing dynamic linking. When your desktop applications call the routines in your DLL, they do so by DLL name and routine names. If the DLL and attendant routines are not found, my application crashes. Even if they are found, if they're not the right version, you can get unexpected results. Hence the term "DLL hell."

Here's a good one. Sometimes, competing software vendors will each produce their own versions of a DLL, and they'll name it the same thing. When replacing software package A with package B, if A's DLLs have a creation date later than B's, they may not get replaced during the installation of product B. So you have the applications of product B and the DLLs of product A.

A COM Code Example: Creating Your Own DLL

As an example of how you can code your own COM objects, a simple ActiveX DLL will be created and then accessed from a couple of calling applications. First, the DLL.

A collection of utility routines that comply with the COM interfacing standards is called an ActiveX DLL. The ActiveX objects in the DLL will have publicly exposed methods and/or properties, and you can create instances of those objects within your COM-aware applications (like those built with .NET languages, VB6).

A simple DLL will be created within VB6 that will figure out what time it is at corporate (Eastern time zone). It will do so by determining which time zone the PC is in and then adjusting the time by the number of offsetting zones. The DLL will get the offset from the PC to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) using the Windows GetTimeZoneInformation API. This API returns the number of minutes between your time zone and Greenwich, England. From that, you can figure out where you are, and in turn, how many minutes you are from the Eastern Time zone.

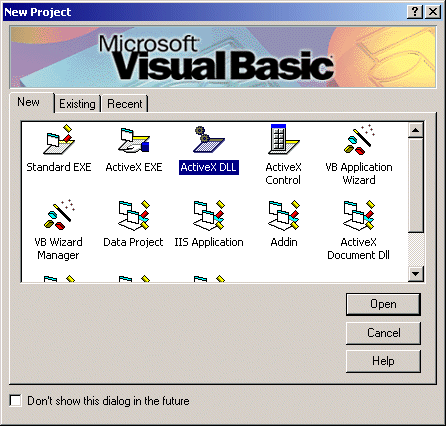

To begin an ActiveX DLL project in VB, start a new project and select "ActiveX DLL" as the project type (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Select "ActiveX DLL" to begin an ActiveX DLL project. (Click images to enlarge.)

You'll be presented with the familiar VB6 IDE. You may notice, however, a different set of properties that are associated with a DLL project. These are DataSourceBehavior, DataBindingBehavior, Instancing, and whatnot. Of these, the Instancing property may be the only one of interest. Instancing refers to the way Windows will create and share the objects in the DLL. For most applications (certainly our humble illustration), the default value of "5-Multiuse" is appropriate and will allow the most efficient use of the code.

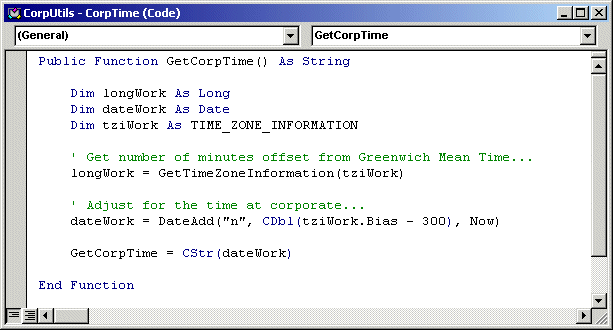

A class within the DLL will have a public method called GetCorporateTime (Figure 2) that will return the time to corporate.

Figure 2: The GetCorpTime function returns the time.

Note that the function is defined as Public. This must be the case for the method to be available to a calling application.

The function returns a string that represents the adjusted time. The adjustment is made in the "tziWork.Bias – 300 statement" (300 being the number of minutes difference between Greenwich and the Eastern zone. The bias, or offset, from GMT is returned from a call to yet another piece--this time, the Windows API routine called GetTimeZoneInformation (for more information regarding the Windows API, see "Microsoft Computing: Introduction to the Windows API").

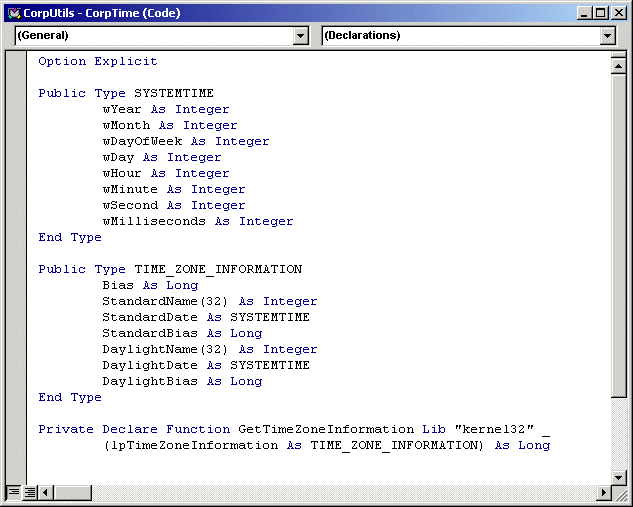

Figure 3 shows the definition of the structures required for the GetTimeZoneInformation API call as well as the declaration of intent to use the API. Note the DLL itself does not require any APIs be used; it's only part of the example.

Figure 3: These structures and function declaration are required to use the GetTimeZoneInformation API routine.

Once the code in Figures 2 and 3 is entered, you should appropriately name your DLL class ("CorpUtilsClass" is used in the example) and your project. The project name is part of the project properties and was set to "CorpUtils" in the example. You'll see where these names are used again in the code for the calling procedure.

OK, that's it. Just compile the DLL by selecting "Make DLL..." from the File menu. Note that the DLL must be available in your PC's folder path or explicitly specified in all calling programs. Most folks choose to create their DLLs in the Windows system folder. For instance, DLLs are created in C:WINNTSystem32 or the equivalent.

Now, you have a COM-compliant object that is universally available to each of your custom desktop applications. All you have to do is call it from some COM-friendly application. To illustrate how that's done, consider the following two examples. One is written in VB6; the other is written in C# and shows how COM objects may be called from a .NET application.

Calling Your DLL

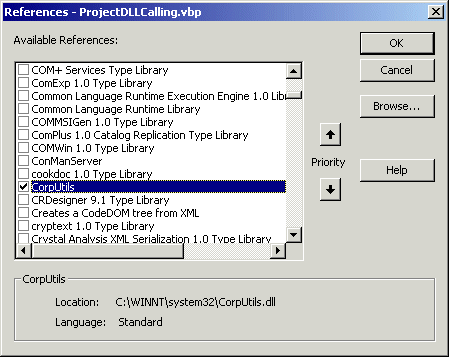

Within a VB6 program, your ActiveX DLL, because it was registered as a COM object when it was created, is available as an object you may reference. So the first step in accessing the DLL's routines from a VB program is to open the "Project references..." dialog box and put a check mark next to your DLL (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Set a reference to an ActiveX DLL from a VB program.

With that done, you can refer to the publicly exposed methods and properties of the DLL as if the methods and properties were coded with your program.

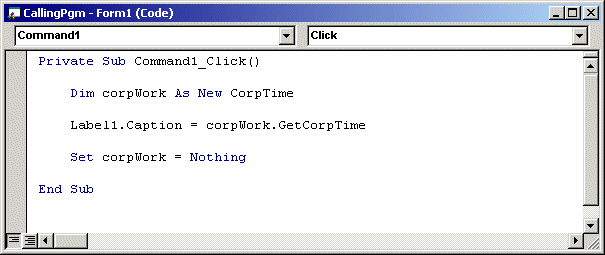

Figure 5 shows the concise code required to call the GetCorpTime method.

Figure 5: This code creates an object of the CorpTime class and executes the GetCorpTime method.

The name of the class--CorpTime--is specified as the type for an object from which the GetCorpTime function may be called. The adjusted time is put in a label on the form for display.

Using a COM Object with a .NET Application

If you're wondering why, in an emerging .NET world, you would create an ActiveX DLL, your point is well taken. In a purely .NET environment, you would not create an ActiveX DLL; you would create a .NET assembly instead. But in the mixed environment where at least some calling applications are of pre-.NET origin, an ActiveX COM DLL can service both environments.

A .NET application can also use an ActiveX DLL. In the following example, a C# program was created to interface with the CorpUtils DLL.

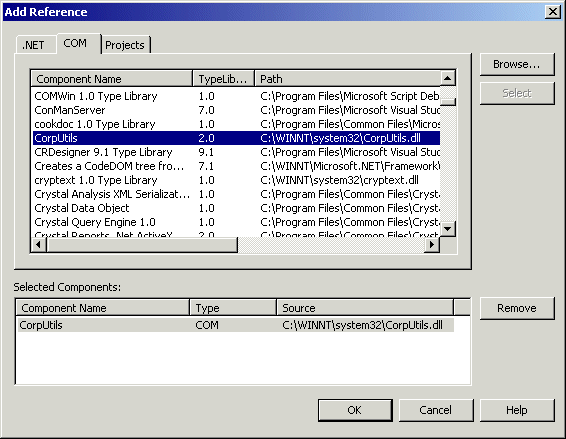

As with the VB6 version, the first step is to set a reference to the DLL (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Set a reference to a COM object within a .NET program.

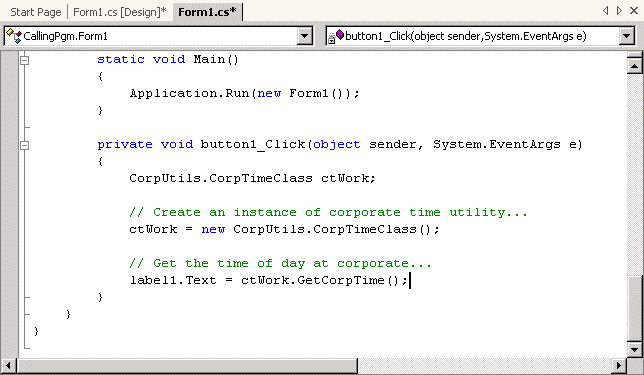

And like the VB code, very little C# code is required to call the methods of a referenced DLL (Figure 7).

Figure 7: This code calls an ActiveX DLL from a .NET C# program.

Again, the example code will call the DLL and display the result of the effort in a label caption. The code to call the DLL from a VB.NET program is very similar.

So there. You've achieved your goal of providing the same service from the same source to a variety of desktop applications. If the DLL requires a change, you only have to modify the DLL's source code in most cases. Further, you may employ COM technology to enforce compatibility limitations between calling and called entities, to help avoid a walk through DLL hell.

In an upcoming article, we'll explore the techniques for producing a .NET shared assembly for native level code reuse among the .NET community.

Chris Peters has 26 years of experience in the IBM midrange and PC platforms. Chris is president of Evergreen Interactive Systems, a software development firm and creators of the iSeries Report Downloader. Chris is the author of The OS/400 and Microsoft Office 2000 Integration Handbook, The AS/400 TCP/IP Handbook, AS/400 Client/Server Programming with Visual Basic, and Peer Networking on the AS/400 (MC Press). He is also a nationally recognized seminar instructor. Chris can be reached at

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online