Now that you know a bit more about Visual Studio and created your first C# program, it's time to see how a C# program compares to an ILE Program.

The previous two TechTips of this series (1 and 2) explained the basics of Visual Studio and helped you create a simple "Hello World" program. Before advancing to more complex stuff, I need to explain the way things are organized in a C# program. Just like an ILE program is composed of procedures and functions stored in programs or service programs, a C# program also follows a hierarchical structure.

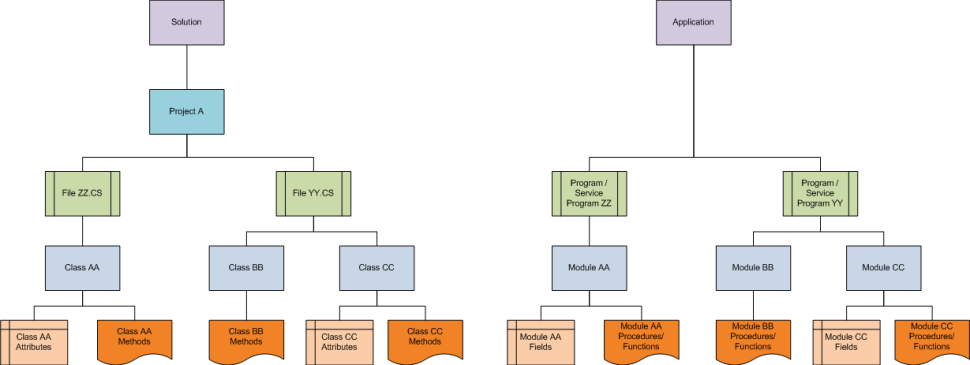

Figure 1 show a rough side-by-side comparison between C# and ILE programs:

Figure 1: Here's a side-by-side comparison of C# and ILE programs.

Let me start by saying that things aren't as directly comparable as they appear to be, but I'll get to that in a minute.

If you look at the right side of the diagram, you'll find the familiar ILE structure: At the top, you'll find an application composed of several programs and service programs. You know that programs can (and most certainly should) use service programs, but that would only bring further complexity into the drawing, so I left it out. Anyway, the programs and service programs are composed of one or more modules, and each module will have several procedures and functions. Even though it's usually not seen as a critical feature, each module can also have its own fields. Some programmers use this feature to provide a set of universally available parameter lists to the procedures and functions of the module, not to store data. Albeit oversimplified, that's a rough representation of an ILE application.

Now let's look at the left side of the drawing. A C# application is called a solution. Each solution can include one or more projects, which are working sets or subprojects of the solution. Unless you're using some sort of development lifecycle management tool, the "project," as shown here, doesn't exist in ILE.

It's here that things start to get a bit tricky: The solution can have one or more files. These are, as you'll see later in this series, not only source files (with the .CS extension), but also configuration and resource files, just like your ILE application might have display/printer files and data areas, for instance. I'll explore what C#'s configuration and resource files are in greater depth later. For now, let's assume, for the sake of simplicity, that a project has only source files. Each of these source files can be composed of one or more classes. Note that even though it's common practice to have a class per file, in some cases, such as GUI-related classes, a class definition will span over several files. Don't worry about that now; I'm just mentioning this so that you don't think there's some sort of unbreakable rule that says "one class per file"!

Continuing to drill down, each class will have its own methods (equivalent to an ILE module's procedures) and attributes, which kind of match the module's fields. I say "kind of" because the attributes are of paramount importance for the class, as they help characterize it. If you recall the notion of class and object, introduced in the prequel to this series, a class is a blueprint of the computer version of a real life "thing"; the article I just mentioned uses a horse to exemplify this concept. The object is a "usable copy" of that "thing," and it's created based on the blueprint —the class. While a module's fields don't necessarily have a strong connection to its procedures, a class's attributes help define the class itself. This might sound a bit mind numbing now, but don't worry; it will get easier in due time.

Even more mind numbing is the fact that a class is, in some ways, also similar to a service program because, among other things, you can't call either directly. You need to use the service program's procedures from within another program. Similarly, you need to create a "copy" of the class (an object) in order to use its attributes and methods. This process of creating an object based on a class is called instantiation, because you're creating an instance of the class. To try to see how this might fit in the ILE side of things, imagine that it's something like using a service program in a program but with the huge difference that you can use only one "copy" of the service program in each program and you can create as many instances of a class as you want. Another interesting thing, which I'll explore later, is the fact that you can define which attributes and methods are not available from the "outside" of the object. Once you bind a service program to a program, all the service program's fields and procedures are immediately available without restrictions (assuming you declared the appropriate prototypes).

The next TechTips will focus on the C# language itself: data types, operators, and more! I know that all this theory might not be exactly what you were expecting, but it's necessary to tackle what waits further down the road.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online