In this column, I frequently refer to Linux as the "Swiss Army knife of operating systems." That title, though well-deserved, is somewhat inaccurate, since the term "Linux" refers only to the kernel proper. Without the toolbox provided by the Free Software Foundation (the GNU software) and the other authors of open-source software (OSS), Linux is more like the handle of the Swiss Army knife. It is the toolbox that adds the knife, fork, and spoon attachments. This month, I'll flip through some of those attachments to solve a few problems that I see mentioned occasionally in the AS/400 and iSeries newsgroups and forums, such as automating FTP transfers to or from an i5 and "scraping" information from reports for further processing.

Does This Sound Familiar?

The new software package that I have mentioned in recent months is typical of proprietary software; you can have anything you want as long as the vendor has either anticipated your needs (it's already in there) or you are willing to spring for the inflated development costs involved with customizations (so the same mods can be sold to many other customers). While I can use JDBC to extract most of what I need from this software, some of the data that I need is produced on the fly by back-end processes. The only method to retrieve this data is by running one of the vendor's supplied programs and then using its "download" function to receive either a fixed-layout ASCII text file or the ASCII text version of one of their reports (similar to the output created by the i5/OS command CPYSPLF). Once the data file is down to the desktop, I need to parse the data (if it's a printed file) and then use FTP to upload the result to the iSeries for further processing. Every time I go through this exercise, I feel as though I've been sent through some time warp to the mid-to-late '80s. I figured that there has to be a better way to accomplish this task, a way that minimizes the impact on the users. As it turns out, there is!

Power and Simplicity

Getting these "export" files to the desktop is straightforward. After the user runs the appropriate program and is notified that the data is ready, she picks a file from the download list and is presented with the standard Windows "File Save" dialog box. Encouraging users to download files to the Windows desktop inevitably results in a surfeit of files, which only wastes space on the backup tapes and Windows server, so it's not a good idea. Instead, I created a share on the Linux-based Samba server for this purpose. Permissions to the share are limited to the appropriate users, so the data files are secured from prying eyes.

Once the file is out of the proprietary system and into a PC-accessible location, how should the user put it into the database? Ignoring the data-scraping issues for now (I'll talk about them later), the normal course of action is for the user to run FTP, either by hand (an error-prone method) or by running a script. What leaves me unenthusiastic about this solution is that it causes more work for the user. Even though it's only one more step, I don't like it. Why not? Because I have to depend on the user to get it right every time, ensuring that I will receive support calls. Since I tire of parroting, "Did you run program X after running that program?" I want everything to be as automated as possible.

Rummaging through the GNU/OSS toolbox, I found a program called dnotify. This tool provides for directories what a trigger provides for a database file: the ability to act whenever a change is detected. This simple utility is quite powerful and can watch one or more directories, recognize any combination of changes (such as when a file has been created, deleted, modified, or renamed or has had its permissions changed) and then act on those changes. The command to use dnotify is simple:

When running, dnotify will watch the directory (or directories) that you specify, and if something changes, the command you specify will be called and the name of the directory that had the change will be passed as a parameter. Once your command has completed execution, dnotify will patiently await the next event. In the example, I have instructed dnotify to run the_command_to_execute whenever a file is created in the directory directory_to_watch.

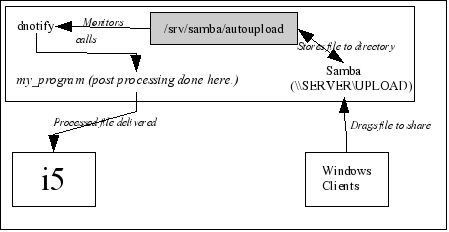

You probably can see where I am going with this. I can trigger execution of a program simply by having the user save the file into a specific Windows share. All that the called program has to do is determine which files have been deposited, perform any processing needed to get them in shape for the iSeries, send the data to the iSeries, and then tidy up and await the next arrival. (The whole thing is illustrated in Figure 1.)

Figure 1: This diagram shows the flow of a file from the Windows user to its final destination on the i5. (Click image to enlarge.)

This all happens asynchronously and without the need to do any polling of the directory. Talk about power and simplicity all rolled up into a neat package! Let's look at the various pieces that I'll need to make this work.

What Changed?

While dnotify can tell you that a change has occurred, it can't tell you what has changed. The called program gets only the name of the directory that changed. It's up to you to figure out what change triggered the event.

For this scenario, my needs are simple. I need to know that a file has been added. How can I tell which file has been added? For that, I'll turn to an open-source programming language called Perl. Originally, Perl was the acronym for the Practical Extraction and Reporting Language (PERL), but it's now referred to as a proper name (Perl). If you have never examined this language, I suggest that you take the time to visit the official Perl home page and investigate it. (You can download it for yourself from that site as well). Sun may bill Java as the write-once, run-anywhere (WORA) king, but I'd argue that Perl has Java beaten for that title. A miniscule sampling of operating systems on which Perl runs (and the ones most likely to be of interest to you) includes Windows, Linux, other UNIX-like OSes, i5/OS, and PASE on i5/OS. Not only does Perl run nearly everywhere, but what makes this language really attractive is the incredible selection of ready-to-use modules and scripts available at the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network (CPAN). If you can dream it, it's likely that someone else has already written and submitted it to CPAN. Perl is at once powerful and simple, clear and obscure, sleek and bloated, easy to learn and frustrating to master. I know there are a lot of contradictions in that list, but that's Perl. If you decide to go "Perl diving," you'll find that you can process a directory as easily as the following code demonstrates.

I have added some comments (anything following a # character) to this Perl code to help you understand it a bit better. Even if you aren't a Perl programmer, I bet you can easily follow the code--one of the advantages of Perl.

use File::Find; # Think of this like a Java "import" statement

#--------------------------------------------------------------

# Process the directory passed to this program.

#--------------------------------------------------------------

sub process_directory {

# DIR is the handle to the directory called "$directory"

opendir(DIR, $directory) or die "can't open $directory";

# This next statement does three things:

# 1) Reads the next directory entry,

# 2) Assigns the name read to the variable $localfile

# 3) The function defined() then returns true if something was

# read or false if EOF

while (defined($localfile = readdir(DIR))) {

# the test '-d $localfile' is true if $localfile is a directory

next if -d $localfile; # no directories

# the next statment employs a Perl regular expression.

next if $localfile =~ /^..*$/; # no 'dot' (.config) files

# If we get this far, the file is interesting to us.

process_file();

}

}

#--------------------------------------------------------------

# Process the file passed to the routine.

#--------------------------------------------------------------

sub process_file {

print "We'd process file $localfile here."

}

#--------------------------------------------------------------

# Entry here

#--------------------------------------------------------------

foreach $directory (@ARGV) {

process_directory();

}

As you can see, there is really nothing to it. If you remove the comments, the total code is only 16 lines (when formatted for reading), so you can tell that there's a lot going on under the covers with Perl. And harnessing that power is done with but a few statements.

FTP Made Easy

Our last script tells us which files now live in the monitored directory, ready to be transferred to the i5. How should we do that? In an earlier column, I wrote about the "expect" utility, for which it would be an easy task to write a script to run the client's FTP program. With Perl, there's an even easier way. How's this for simplicity?

use Net::FTP;

# User credentials for the i5system.

my $i5username = "MYUSER";

my $i5password = "MYPASS";

my $i5system = "mysystem.mydomain.com";

my $localfile = "somefile.txt";

my $remotelib = "MYLIB";

my $remotefile= "MYFILE";

# Make a connection to the server.

# Debug => 1 in the next statement will print the

# ftp dialog with the host system.

$ftp = Net::FTP->new($i5system, Debug => 1)

or die "Couldn't connect to $i5system ";

$ftp->login($i5username,$i5password)

or die "Couldn't login ";

$ftp->cwd($remotelib)

or die "Couldn't cwd to library $remotelib ";

$ftp->put($localfile, $remotefile)

or die "Couldn't put $localfile into $remotefile ";

Perhaps you recognize the FTP commands (login, cwd, put) that are used as method names for the FTP module. The Net::FTP module provides methods to duplicate most of the commands that a standalone FTP client would have, except that this FTP client has a fantastic API that allows you to drive it with more software instead of a keyboard.

You may be wondering about all of that talk of "die"ing. That's one way to handle errors in Perl. Anytime one of those statements fails, the associated die instruction will echo the error message to stderr. As before, I'm sure that you'll have little trouble following the code.

With the "expect" utility, I would have had to do quite a bit of additional work to produce the correct dialogue between the systems. Using Perl, the code has been reduced to roughly five lines, an immense savings of time and effort. (I have all of my values assigned to variables and use the variables in the method calls. You can reduce the line count by embedding the strings directly in the method calls.)

Report Scraping

So far, everything we've wanted to accomplish has been trivial. But what about report scraping? (For those of you old enough to remember screen-scraping, what would you call extracting data from a report?) By "report scraping," I mean extracting data from a textual representation of a printed report that contains headers, footers, subtotals, totals, and other decorations. How can we get the report data into something usable on the i5?

Certainly, there are commercial products capable of extracting data from reports. One common example is Datawatch Corporation's Monarch product, an extremely powerful tool to be sure. While intriguing, Monarch is definitely overkill for a project such as mine. That the acronym PERL means "Practical Extraction and Reporting Language" should give you a clue as to the language's original purpose, so it should come as no surprise that extracting data from a report is a task at which Perl excels.

Before I show you the code, let me explain what the text file looks like. The file I get is a combination of four separate reports, each of which contains similar types of data. The title line in the report heading changes as each of the four report types is printed. Naturally, not all columns appear on each version of the report, and, of course, the columns that appear on more than one report don't appear in the same print area. So parsing this text file can be somewhat problematic. Here's the code:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

# These fields will be used as "keys" into the hash table below

my $NO_READING = 'NO_READING';

my $TOO_MANY_EST = 'NO_EST';

my $NEW_CONNECTS = 'NEW';

my $UNKNOWN = '*';

# This is a hash table. Think in terms of an array with a named

# key and you'll get the idea. For example:

# $masks{'NO_EST'} returns 'A10 x2 A20 x1 A4 x10 A9 x26 A5'

my %masks = (

$NO_READING => 'A10 x2 A20 x1 A4 x10 A9 x22 A5',

$TOO_MANY_EST => 'A10 x2 A20 x1 A4 x10 A9 x26 A5',

$NEW_CONNECTS => 'A10 x2 A20 x1 A4 x10 A9 x22 A5',

$UNKNOWN => 'ERROR: Record data screwed up.'

);

# Fields to be extracted

my ($account, $pole, $rate, $last_reading, $mtr_nbr);

my $record_type = $UNKNOWN;

# This while loop reads the text piped through stdin one

# line at a time.

while ( <> ) {

# Look for a heading line to determine the column layout.

$record_type = $NO_READING if /^ +THESE ACCOUNTS DO NOT HAVE A

PRESENT READING AND ARE CODED DO NOT ESTIMATE/;

$record_type = $TOO_MANY_EST if /^ +THESE ACCOUNTS WILL EXCEED THE

MAXIMUM NBR OF CONSECUTIVE ESTIMATES/;

$record_type = $NEW_CONNECTS if /^ +NEW CONNECTS AND RECONNECTS/;

# Now look for what we RPG programmers would call a detail line.

if (/^d{10}/) { # detail lines start with the account number

# Extract the fields using the appropriate mask. Yep, all 5

# values are assigned simultaneously.

($account, $pole, $rate, $mtr_nbr, $last_reading) =

unpack($masks{$record_type}, "$_");

# The chomp function is basically a trim() function for Perl.

chomp($account);

chomp($pole);

chomp($rate);

chomp($mtr_nbr);

chomp($last_reading);

# This will dump tab-separated fields to stdout.

print "$record_type $account $pole $mtr_nbr $last_reading $rate ";

}

}

Think about how much effort you'd have to expend to do this sort of task in other languages, and you'll soon gain an appreciation for the power of Perl. And this program is by no means to be held up as a prime example of proper Perl coding. (Talk about an understatement!) Masters of the language could boil this code down much further. But in this form, it is more illustrative than a Perl-language blackbelt's rendition would be.

Just What I Need... Another Language to Learn

After reading this article and checking out CPAN, you may be intrigued by Perl but hesitant to take the time to learn yet another language. Well, you can quickly pick up the language with the addition of two books to your library.

The first is called Programming Perl by Larry Wall, Tom Christiansen, and Jon Orwant. This book is the definitive work on Perl (as it should be, since Larry Wall is the creator of the language) and is written in an approachable and downright humorous style. It makes a good read if only for the humor!

The second book is titled Perl Cookbook by Tom Christiansen and Nathan Torkington. This tome is filled with case studies on various problems and their Perl solutions in typical cookbook fashion. It, too, is irreverent but extremely useful--so much so that it's the first place I look when wanting to apply Perl to a problem.

These books will make you productive within a few hours and will pay for themselves quickly, so I highly recommend them. And the addition of Perl to your programmer's toolkit will pay for your time spent as well.

Why Even Try?

I've been programming on the System/38, AS/400, and iSeries for over two decades, so I've written my share of code. While I like CL well enough (especially since the newer enhancements have made it more useful than before), I still find that so many of the simple tasks I do take far too much effort to accomplish using CL alone or in conjunction with RPG. Open-source tools such as I have described make seemingly complex tasks easy to accomplish, and IBM's integration of these tools with the i5/OS make their use seem logical and natural. As I've said before, open-source software has such a low entry cost and universality that it is going to be hard to ignore it for too long. Do you agree?

Barry L. Kline is a consultant and has been developing software on various DEC and IBM midrange platforms for over 23 years. Barry discovered Linux back in the days when it was necessary to download diskette images and source code from the Internet. Since then, he has installed Linux on hundreds of machines, where it functions as servers and workstations in iSeries and Windows networks. He co-authored the book Understanding Linux Web Hosting with Don Denoncourt. Barry can be reached at

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn: Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online