This is the last article in a three-part series about IBM's On Demand business transformation model. In the first article, I discussed the traditional IBM view of the strategic IT organization and why that view met its demise in the late 1990s. In the second article, I examined IBM's evolving vision of business transformation that has led it to a so-called On Demand architecture and infrastructure. I also talked about how IBM believes that standards-based software, open-source technologies, and IT consolidation can help organizations stair-step toward this On Demand environment.

However, all this business theory may sound like folderol unless IBM can distill the concept of an On Demand evolution into a real business plan. Moreover, it's one thing to create a theoretical basis for business transformation, and it's quite another to build the IT infrastructure that realistically supports that transformation. So, in this article, I'll try to put some fur onto this beast called "On Demand" and provide an example of how--from IBM's perspective--the steps leading to an On Demand environment can significantly transform the way organizations do business in the future.

Finally, I'll look at what IBM believes is the current state-of-the-art configuration of an IT infrastructure supporting an On Demand business enterprise.

An Example of an End-to-End Part Design

When IBM executives talk about the On Demand business transformation model, they almost always start with the customer's requirements for service: They put themselves in the customer's shoes and extrapolate backward to develop the systems that meet those requirements. In other words, they don't sit in their ivory towers and conjugate technical protocols; instead, they think about what their customers' customers are demanding. Here's an example of how they might envision one On Demand requirement:

"What if your customer, who makes refrigerators, wants to build a cheaper product by creating new, interchangeable standardized parts across its entire product line? This refrigerator company doesn't want to engineer these parts in-house; they want to out-source the entire design process to an engineering firm. They also don't want to create a large stockpile of inventory of any particular part, because modifications to the design will be ongoing as their refrigerator design evolves to meet the criteria of their marketing research. They want to be able to redesign all of the current products using a similar On Demand model. How do you build a process to meet this kind of custom, On Demand manufacturing in a supply chain?"

Evolving Toward Custom Manufacturing

For a company that manufactures widgets for refrigerators, this kind of manufacturing is what once might have been perfect for a "custom job shop" environment. It's not what one normally thinks of as an "assembly line" or "inventory" part. Custom jobs are usually "bid" jobs: The profits are typically slim because the setup time is intensive and the number of orders for the production run is usually limited.

However, in this On Demand environment, the refrigerator customer is requiring the widget manufacturer to be as responsive to changes in design specifications and order quantities as a custom job shop. They want their "service" from the widget supplier to be representative of their enterprise requirements.

Consider too that this kind of service is precisely what traditionally drives up the cost of manufacturing and, in many cases, sends refrigerator manufacturers searching for the lowest-cost supplier with the most responsive (and lowest paid) workforce.

The IT Dilemma for On Demand Manufacturing

Technically, this kind of environment requires a significantly different kind of IT infrastructure than the traditional, more static environment in which designers design, manufacturers manufacture, inventory clerks perform inventories, and shipping clerks ship products. Instead of the "fixed" organizational boundaries between the supplier and the customer that typify most business relationships, the On Demand boundaries are permeable, and the requirements for cross-organizational collaboration are significant.

The widget designers must have a special ability to collaborate with the refrigerator company's designer team of out-sourced engineers; the manufacturing team must have a special collaborative ability with the refrigerator company's marketing department; so too must the inventory department and the shipping department be responsive to flow of widgets to meet the fluctuating delivery demands to the many different assembly destinations. The information system that could support this kind of collaboration will--from IT's perspective--require a completely different, more responsive set of triggers, triggers that emanate from outside the boundaries of the widget organization itself.

Without a doubt, from IT's viewpoint, transforming the widget manufacturer--with a traditional IT infrastructure--to become a collaborative business partner with the On Demand refrigerator manufacturer will require a significant investment in both new technology and new internal business rules. Such a budget is certainly outside normal operating parameters.

However, from the CEO's perspective, if such a business transformation were possible, it would catapult the widget manufacture's fortunes--not only with the refrigerator manufacturing company, but with all of the widget manufacturer's customers.

IBM's Transformation Blueprint

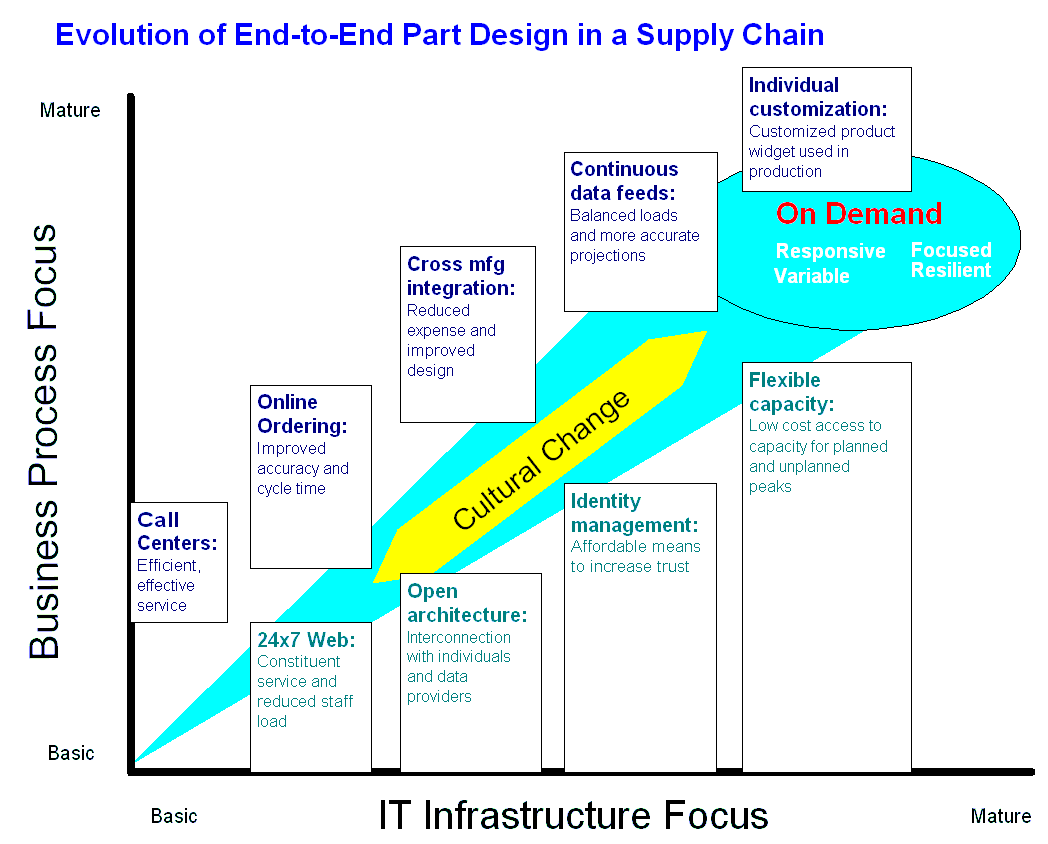

This is the vision of the On Demand environment that IBM has conjured and the dilemma that faces current IT departments and their companies. But, according to IBM, companies can make the necessary steps toward On Demand environments by using IBM's consolidation stair-step approach. An IT plan to get to this On Demand infrastructure for our example might look something like this:

(Click images to enlarge.)

At the basic level, the widget manufacturer might currently have a call center to take customer orders for existing products and process those orders through the existing IT systems. Subsequently, the manufacturer might have instituted an online ordering system over the Web. This system increases the accuracy of new orders while decreasing the cycle time necessary to process them. To support these initial steps toward the On Demand system, there's a 24x7 Web site. According to IBM, the savings in personnel cost and increased accuracy should be plowed back into the next step of automation: cross-manufacturing integration.

In the cross-manufacturing integration system, a cross-organizational design system is shared between the widget manufacturer and the primary customers. It might start as a simple online design program, or it might be a full set of collaborative design services that use open-source standards to tie into the refrigerator manufacturer's CAD programs. The point is that IT has positioned the organization for this kind of collaboration by relying upon applications and systems that support an open architecture through open standards. Meanwhile, in the background, the cultural change within the widget company reflects a new requirement: that engineering teams from separate organizations collaborate and respond to the demands of custom design coming from the outside business partner. The savings realized by this step should--from IBM's perspective--support the next IT consolidation step: identity management.

With some affordable identity management software and security, the organization can expand the cross-organizational collaboration capability to other customers. This step expands the customer base--and the organization's profits--while maintaining the security of the overall custom-design processes for each customer. It is at this juncture that the reliability of the IT infrastructure becomes increasingly important, while at the same time, utility-like services for capacity management start to make financial sense. Providing some means of continuous capacity flow of orders and designs--server load-balancing, automated customer response mechanisms, and "self-healing" (autonomic) networking systems--could significantly reduce the costs of operating the overall mechanism. So IT consolidates again, toward the On Demand goal.

The end evolutionary point--as IBM envisions it--would be a system by which the refrigerator company (or any widget customer) could embed the widget manufacturer's On Demand engineering and manufacturing services into their own design and manufacturing processes. (As an example, imagine the engineers sending down tooling specifications directly to the widget manufacturing equipment.) The products coming off the manufacturing lines would thus prove to be, according to IBM, responsive to customer demand, variable to different product requirements, resilient to changing specifications, and focused to the specific needs of the end customer.

In the meantime, the widget manufacturer would have transformed the business model of the organization, step by step, with a moderate reinvestment in technology through consolidation toward a specific architectural goal that could provide it with a new strategic advantage in the marketplace: It would have become itself an On Demand custom manufacturer that could produce design-sensitive widgets in a time-sensitive manner.

The Enterprise On Demand Model

OK, so maybe this On Demand model of IBM has some potential legs, right? Perhaps, rather than just raw business theory, it has some practical application as well. From an IT perspective, what might such an On Demand infrastructure look like?

To comprehend the scope, IT has to step outside of the limited world perspective of widget manufacturing and see the larger enterprise of its own supply chain. Instead of seeing the world in iSeries- or Windows-compliant bits and bytes, it has to see how its information flow will fit into the larger structure of an enterprisewide On Demand system.

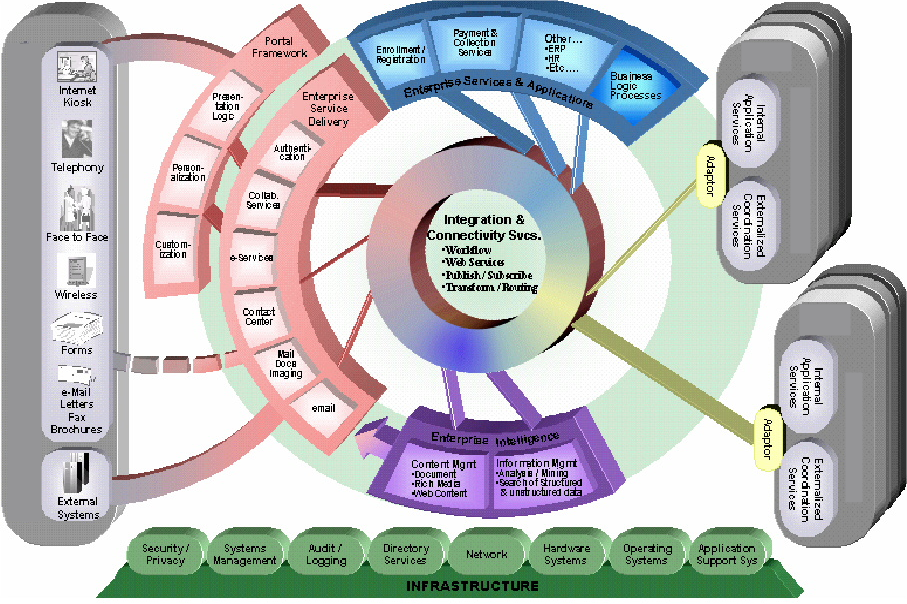

IBM's own model--the one it uses to communicate to large, enterprise organizations--might serve to give us that perspective.

On the left side of the model, customer access to the On Demand model is represented by a set of services (Internet, telephony, wireless, etc.) leading through a layer of access services (portal framework and "Enterprise Services") to a central hub of integration and connectivity services. These central services tie together the operational and decision-making mechanisms of the On Demand organization. On the right side are the suppliers, each responding to the needs that the central On Demand organization is sending to it. The widget company in our example would represent one of those suppliers on the right.

Note that, in this IBM schematic, the IT infrastructure itself is separated into a series of discrete services (in green) each delivering some essential benefit to the overall architecture. There's no identification of "platform" or technical protocol; instead, there's a generic label of a technology, like "Systems Management," "Directory Service," "Hardware Systems," etc. This is important because it is the key to understanding why IBM is stressing open-source and international standards: You can't build such a collaborative enterprise with proprietary software or hardware.

If our widget company builds its interface along the lines of open-source and international standards, then it can become a supplier to not only one supply-chain customer, but multiple enterprises, responding uniquely to each one as required.

Final Analysis: Is On Demand for Real on the iSeries?

IBM has invested a lot of engineering and marketing collateral into pumping up the On Demand model for larger enterprises, companies, and governments. But, in the final analysis, the business model for transformation may not fit for many iSeries customers. Why?

First of all, the cultures surrounding organizations who use the iSeries is often quite provincial: Many iSeries companies see themselves as the hubs of small supply chains or a customer relationships and have no desire to transform. The impetus to move to an On Demand environment may not be a good investment strategy if there are no outside pressures driving them to the On Demand model.

Second, the iSeries is already a highly consolidated platform--a platform that has a long history of past consolidations. These legacy services may not be as flexible or resilient enough to move toward open-source applications and might require significant reinvestment before they can do so.

Third, the iSeries continues to receive new technology from IBM at a slower rate than other platforms--not necessarily on the code level, but on the educational level. It continues to be hard for iSeries professionals to obtain the educational courses they need in order to implement the technologies that an On Demand environment requires.

In other words, as stable and as resilient as the iSeries has proven to be over its long evolution, most iSeries management's commitments to expanding the use of the platform have been anything but "On Demand."

Furthermore, convincing an organization to use the iSeries in "nontraditional" ways is not anywhere on IBM's agenda. Using the iSeries as a consolidation mechanism, however, is. Consequently, you will continue to see IBM Rochester (home of the iSeries) stressing the box's ability to consolidate services, but you will seldom hear IBM talking about building enterprise-level On Demand environments using the box as a central hub.

And that, in the final analysis, is exactly what the IBM On Demand initiative is about: transforming business models, not transforming legacy boxes (no matter how resilient).

Making IT Strategic Again

Likewise, if IT is to be successful at stepping up to the strategic challenges of their company's business model, IT must stop focusing on the capabilities of any particular piece of hardware or software. Instead, it will become increasingly important for IT to look at the larger On Demand model of the real-world collaborative environments. This, according to IBM, is where every organization must now learn to work: across server platforms, operating systems, applications, languages, and protocols. That's IBM's chief rationale for selling so many platforms, and that's the reason they are chanting the open source, international standards mantras to anyone who will listen.

If IT can muster the courage to transition away from "technical preferences" and toward "business goals," it has an opportunity to lead. It has a chance to once again become the strategic department within the organization, helping management achieve its goals. If it neglects this task, it will continue to suffer, it will continue to see its resources stripped or outsourced, and it will ultimately become just another expendable cost center as the organization moves to the On Demand model.

That, at least, is where IBM's On Demand initiative leads.

Thomas M. Stockwell is the Editor in Chief of MC Press, LP.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online