Replication is available in two generic flavors, hardware-level and logical. Yum. But which should you choose? It all depends. Or you can have it all.

Replication is a familiar thread in the modern information technology infrastructure fabric. It serves a number of purposes, including the following:

•· Provide for high availability (HA) and disaster recovery (DR) by creating real-time or near real-time replicas of production databases, files, system values, and applications. This is probably the most prominent replication use but certainly not the only one.

•· Integrate applications at the data level by sharing information among application databases.

•· Stock data warehouses and data marts by copying data into them from operational databases.

•· Improve load balancing by creating a secondary data store that can support read-only operations. Depending on the type of replication used, this can be an automatic supplementary benefit of HA replication.

Painting a broad-brush picture, there are two generic flavors of replication: logical and hardware-level. Logical replication is available in a few sub-varieties. HA software includes replication functions that typically maintain exact duplicates of a primary server's data, system values, and applications on a second server. If that backup server is in a remote location, it can also keep the business running after a disaster strikes the primary data center.

Some DR solutions, such as data vaulting, provide disk-to-disk logical replication functions similar to those found in HA software, the difference being that the copy cannot facilitate a ready-to-run backup server. Before business operations can resume, the backup copy of the data usually has to be loaded into databases and the server has to be configured.

Another form of logical replication is found in standalone data replicators used to share information among disparate application databases or to load data warehouses and marts from operational databases. Typically, these operate solely at the database level and replicate only application data--not system values, programs, or other objects.

The word "replicate" can be misleading in the case of standalone replicators. Rather than creating true replicas, i.e., exact copies, these products can often transform data as it moves from one location to another, and they can usually copy data from one brand or version of Database Management System (DBMS) to another one. This is essential when trying to share data among disparate applications on diverse platforms as you need a way to accommodate differences between the various databases.

Transformation capabilities, along with the ability to map data between different database schemas, are also useful when using replication to stock data warehouses and marts. For example, because the data warehouse merges data from a number of sources, transformation functionality is required to reconcile the differences among those sources. In addition, data warehouses are often de-normalized for performance reasons. If not, the analytical functions that are usually performed on data warehouse data would require a great number of massive, costly data joins. Data mapping functionality is required to accommodate this de-normalization.

In addition to the standalone variety, a replicator is often built into or is an available add-on for a DBMS. Whether or not a DBMS replicator can transform data or replicate to other DBMS products depends on the DBMS.

In the IBM i world, hardware-level replication is normally performed using IBM's clustered storage replication technologies. These are sold under an umbrella brand of Cross-Site Mirroring (XSM), which includes three distinct capabilities with different characteristics: Geographic Mirroring, Metro Mirroring, and Global Mirroring. (For more information on implementing IBM hardware-level replication, please see the IBM Redbook IBM System Storage Copy Services and IBM i, A Guide to Planning and Implementation.) Alternatively, if you use EMC Symmetrix external storage arrays, hardware-level replication can be performed using EMC's Symmetrix Remote Data Facility (SRDF).

With that brief tutorial on replication, the next question to address is, "Which should you choose, hardware-level or logical replication?" The answer is, "It all depends." The first issue you have to consider is the objective you are trying to achieve.

Ends Limit Means

To deal with the most straightforward purposes first, consider replication to share data among diverse application databases or to feed a data warehouse or data mart. In those cases, logical replication is almost certainly your only choice. Invariably, either of these ends requires some transformation capabilities to handle the structural and format differences between the source and target databases, possibly including differences in the DBMS brand. Hardware-level replication cannot fulfill these requirements.

Likewise, these purposes also typically rule out replicators inside HA software because they create exact replicas without offering transformation capabilities.

Fulfilling HA/DR Objectives

Hardware-level and logical replication each has its strengths when it comes to serving HA and DR purposes. A November 2007 IBM Redbook, Availability Management: Planning and Implementing Cross-Site Mirroring on IBM System i5, provides the following summary of the differences between the HA traits offered by Cross Site Mirroring's (XSM) hardware-level replication and by High Availability Business Partners' (HAPB) logical replication solutions:

|

XSM vs. HABP |

||

|

|

XSM |

HABP Solutions |

|

Switchover Time |

Minutes |

Less than 30 minutes |

|

Failover Time |

Minutes |

Less than 30 minutes |

|

Based on Journaling |

No, but journaling is highly recommended to ensure data integrity |

Yes |

|

Data on Target System Usable in Normal Mode |

No |

Yes, read-only |

|

Resynch Time After Use of Target Data |

Hours (less time required with V5R4 and Target Site Tracking) |

None (if read-only) |

|

Supported by OS/400 Cluster Services |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Object Types Supported |

Limited |

Most |

|

Save/Restore Required for Initial Setup |

No |

Yes |

The switchover and failover times in this table bear some explanation. The HABP value is correct; in fact, those solutions can often failover or switchover in considerably less than 30 minutes. The actual switching of the direction of journal replication occurs in much less than a minute, and the database is already accessible for reads even while it is serving as a backup, so removing the lock on writes is the major action that must be taken during the switch. The rest of the time in the "less than 30 minutes" is a pessimistic view of the possible lag in journal applies that might have accumulated prior to the switchover or failover. The 30-minute estimate also allows for the possibility that a synchronization check of the data will be required before giving users access. The reality is that HABP solutions typically provide the shortest switchover or failover times because the target-side database is already active and available for use when the application is brought online.

The quoted XSM switchover/failover times are, however, very optimistic. In those environments, to complete a failover or switchover in "minutes," everything has to be perfect. And that is almost never the case.

XSM technologies require a "vary on" of the switchable Independent Auxiliary Storage Pool (IASP) before the backup server can access the data and assume operations. When an IASP (the primary storage area in an XSM-mirrored environment) is varied on, internal checks are run to ensure that the information on the IASP is compatible with information on the system. For example, you cannot have the same library specified in SYSBASE as you do in the IASP. If there are conflicts, the request to vary on the device will fail, rendering it unavailable to the system until the library is removed from SYSBASE or the IASP. In fact, the IASP vary on process includes 32 steps that perform the various audits required to guarantee that the IASP can be made available. These steps can be observed with a DSPASPACT command while varying on an IASP. Unless you have a very simple database, it will take considerable time to audit and resolve all necessary changes associated with moving an IASP from one system to another.

As noted, there are situations that will prevent a successful switchover. Thus, audits performed by third-party software are beneficial to continuously monitor all possible conflicts. Consequently, under real-world conditions, failover and switchover times are generally much shorter for HABP solutions than for XSM solutions.

Second-System Capabilities

One advantage that XSM offers that is not listed in the table is a somewhat greater ability to protect data integrity. The IASP copy maintained by XSM on a second system or on a second partition on the primary system is controlled entirely by the primary system or partition. As a result, there is no way for a user to tamper with the backup copy through the second system or partition. In contrast, when using logical replication, at the HABP level there are ways to lock out any user activity that would write to the database copy while the replication function is active, but IBM i does not provide the ability to keep it locked at other times.

This control of both copies by the primary system may be a data integrity benefit, but it comes at the price of reduced flexibility. When using logical replication, the backup copy is under the control of the backup system or partition. This leaves you free to shift read-only processing--such as queries, reports, and tape backup jobs--to the backup system, thereby reducing the load on the primary system and, because backup jobs can be run on the secondary system, reducing the required backup windows. Consequently, you may be able to use a logical replication solution to defer server upgrades. This load-balancing capability is not available in a hardware-level replication environment because the backup system cannot access the backup disks until they are varied on.

Geographic Limitations

If you will be using replication to provide a means for your organization to recover after a disaster (DR) or to continue operating throughout a disaster event (HA), the replication source and target servers must be separated sufficiently such that a disaster will be unlikely to affect both locations. This requirement does not eliminate either hardware-level or logical replication, but it does limit the choices within those two categories.

The speed of data transmission over a network is orders of magnitude slower than the speed of data transmission within a server. These network delays increase with distance and with the number of routers, switches, and other communication devices that the data must pass through.

Synchronous replication locks the application that updated the primary database until the update is replicated to the target server and an acknowledgement is received at the source. Thus, synchronous replication is impractical when the distance between the source and target database is great because user response times would lengthen unacceptably. The definition of a "great distance" varies based on a number of factors, but, as a general rule of thumb, it is usually impractical to use synchronous replication over distances of more than 50 miles. Keep in mind that this is only a rule of thumb. If the transaction volume of a particular application is especially heavy, even distances of as little as two miles may unacceptably degrade the performance of the application.

Synchronous replication is a function of remote journaling and is usually an option that can be turned on or off in HA replicators that use remote journaling. It may also be an option in a replicator built into a database. It is much less likely to be available in a standalone data replicator and is rarely, if ever, available in DR products. Looking at hardware-level replication, IBM's Metro Mirroring offers only synchronous mirroring. Geographic Mirroring provides both synchronous and asynchronous options, but the asynchronous mode still requires an acknowledgement from the target system (and is thus, in effect, still synchronous). Global Mirroring offers asynchronous replication. EMC's SRDF family includes asynchronous (SRDF/A) and synchronous (SRDF/S) products. (EMC also offers SRDF/DM, which performs incremental, point-in-time data copies non-synchronously, without the need for a server on the target side.)

Replication Completeness

As the product category descriptor implies, standalone data replicators replicate only data. This is sufficient for the types of tasks these replicators are called upon to do--sharing data and stocking data warehouses and marts--but HA requires a more complete replication schema. In addition to application data, all programs and system objects must also be replicated to the backup system if it is to be immediately ready for use when needed. HA logical replicators typically rely on either local or remote journaling to capture data changes on the primary system. Remote journaling also serves as the transport mechanism for moving data to the backup server. HA logical replicators that use local journaling generally use proprietary mechanisms for moving data to the backup server.

HA logical replicators normally use the system audit journal to capture and replicate changes to objects that are not supported by IBM i data journaling. Combined with the changes captured and transmitted from the database journals, the result is a functionally complete backup replica.

Hardware-level replication, on the other hand, may not be as complete. For example, IBM's Geographic Mirroring product replicates only data in IASPs, which is not the full set of objects required to maintain a ready-to-run backup server. The list of supported object types varies depending on the release of the operating system you are using. You can find the list of supported objects for IBM i (OS/400 or i5/OS) 6.1, V5R4, and V5R3 at the IBM Web site.

IBM i offers an administrative domain for some unsupported user objects and system attributes. Administrative domain replication allows both hardware-level and logical replicators to expand the variety of objects they can handle.

Application and Transaction Awareness

Business applications typically use a database, IFS files, data queues, data areas, and related objects such as spool files, user profiles, programs, passwords, directory entries, and other object types. Unlike hardware-level replication, which replicates data blocks without regard to how they are being used, HA and standalone replicators can be application-aware. When using HA or standalone replicators, it is, therefore, often possible to halt replication for a single application while allowing it to continue for others. You can use this replication granularity to, for example, back up a human resources application in the middle of the night while a manufacturing application continues to run on the same system.

In many cases, granularity below the application level is also required. You often also need the means to protect the integrity of individual transactions.

Hardware-level mirroring replicates and applies all uncommitted data to the backup disk volume. Thus, when a system failure occurs, partial transactions may have been applied to the backup disk. Consequently, after a failure you must first verify transaction integrity and attempt to repair any problems before the data can be used.

Because the repair work is usually a cumbersome custom process, it is time-consuming and introduces the risk of human error. Furthermore, it is not always possible to repair all business transactions. Although not a technical requirement, to provide a remedy for possible problems associated with a commit cycle, IBM recommends journaling all transactions when using IASP-based hardware mirroring.

In addition to the problem of transactions that are half-complete at the time of a failure, because hardware-level mirroring cannot identify damaged objects on the production disk volume, it will blindly replicate corrupted data to the backup disk. Data corruption caused by damaged objects, which, in a hardware-level replication environment, may not be detected until sometime after the damage has occurred and many additional transactions have updated (or attempted to update) the corrupted data, cannot be easily repaired. In contrast, HA replication products may include self-checking and self-healing features that can detect damaged objects and automatically correct them.

Hardware Flexibility

Not only is logical replication not performed at the hardware level, but it is not even hardware-aware, at least not as far as disks are concerned. This is an advantage in that it allows much greater flexibility when buying disks. You are free to mix and match products from different vendors on both sides of the replication processes.

In contrast, hardware-level replication often limits the disks you can use. For example, EMC's SRDF can replicate only from and to EMC Symmetrix disk arrays, and IBM's Peer to Peer Remote Copy (PPRC), which underlies many of IBM's hardware-level replication solutions, can only replicate from and to IBM external disk arrays.

Synchronization Issues

In the past, the possibility that the primary and backup databases might become unsynchronized was used as an argument against logical replication and in favor of hardware-level replication. Over the past few years, this issue has all but disappeared. Ongoing IBM i journal enhancements have allowed the HABP products to steadily close the holes and thus make a lack of synchronization much less likely than it was in the past. In addition, many HA logical replication products now include automatic synchronization checking and remediation features that virtually eliminate any chance that an out-of-synch object will go undetected and unresolved for more than a very short period.

Hybrid Solutions

Replication doesn't have to be an either-or decision. You can choose both logical and hardware-level replication.

A number of companies have implemented hybrid solutions that apply the best technology for each circumstance, thereby increasing the HA protection of the solution.

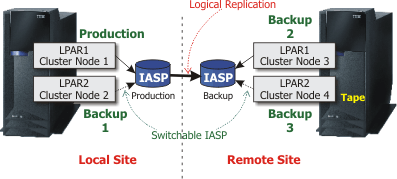

Figure 1: Hybrid solutions amplify flexibility and availability.

For example, some organizations are taking advantage of IBM i clustering to install a combination of switchable IASPs and logical replication, using three or four nodes in the cluster. As a result, the production site has a backup logical partition that can be made available to receive the production IASP disk volume or disk files when switched between logical partitions on the same system. Simultaneously, logical replication is used to maintain a second copy of the data on a system at a second site. That site may also have a second logical partition that can receive the backup IASP disk volumes.

There are a number of advantages to this hybrid approach. In addition to the obvious DR benefits, two or three backup systems allow for continuous HA support when one node is down for maintenance. In practical terms, the cost of the backup systems can be relatively low because they can serve multiple roles while not requiring any more disk.

So Which Way to Go?

In conclusion, there is no definitive answer to the question, "Should you use hardware-level or logical replication?" The most appropriate response depends on your environment and on what you want to achieve. And it is not a binary decision. You don't necessarily have to choose one or the other. Within a single organization, there might be some purposes that demand logical replication, while others may be better handled by hardware-level replication, and still others may be best served by a hybrid solution.

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn: Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online